In the waning days of Hong Kong’s 2014 student-lead Umbrella Movement, a hanging black banner read a prophetic message: We’ll Be Back. In 2019, those words came to fruition. The controversial introduction of a proposed extradition bill, allowing individuals in Hong Kong to face trial in Mainland Chinese courts, rocked the city and drew hundreds of thousands to the streets. Antony Dapiran’s City on Fire masterfully gives life and insight into the protest movement as well as the uniquely Hong Kong characteristics that developed along the way.

Dapiran, a Hong Kong-based Australian lawyer and writer, is one of the leading observers of Hong Kong’s long history of protest and dissent. His previous work, City of Protest (2017), chronicled the former British colony’s earliest days of dissent, all the way to continuing legal battles that ensued after the aforementioned 2014 movement. Dapiran witnessed firsthand the events taking place in Hong Kong in 2019 and provides a level-headed analysis and assessment of the movement as it transpired.

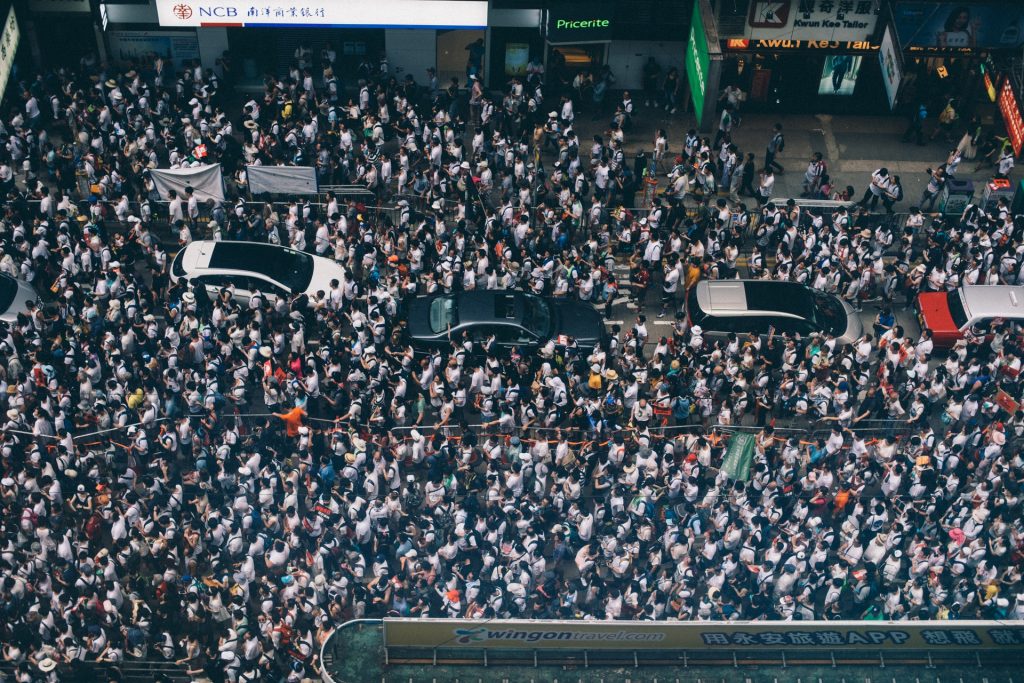

Fierce criticism erupted when Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced in early 2019 that the city would initiate the legal process to enable extradition of individuals residing in Hong Kong to the Chinese Mainland. Despite pushback from even customarily pro-establishment voices like the city’s business sector, Lam forged ahead, bypassing traditional practices in hopes of expediting the law. Tensions came to a head on June 9th when an estimated one million people took to the streets to voice their opposition. In subsequent weeks as protest continued, the movement evolved; Dapiran notes, “what began as fight against the extradition bill became something more than that: a fight for the very soul of the city.”[1] The focus shifted from simple opposition to the proposed bill into five concrete demands: full withdrawal of the extradition bill; a commission of inquiry into alleged police brutality; retracting the classification of protesters as rioters; amnesty for arrested protesters; and, the ultimate goal, full universal suffrage.[2]

Learning from their experiences five years prior, Hong Kong protestors adapted. No single participant stood out as the movement’s leader, channeling local hero Bruce Lee’s strategy of “Be Water.” With the protestors clad in their signature black attire and yellow hard hats, the approach called for them to form smaller groups who, “with no entrenched positions and adopting an unpredictable and constantly mobile presence…[could] simply disperse and regroup elsewhere later if they met with police opposition.”[3]

As one of the most densely populated cities on earth, Hong Kong lacks many of the wide-spaced public grounds that often act as key gathering points for social movements. However, protestors found ways to adapt. The answer lied in shopping malls. As Dapiran points out, “Hong Kong has the highest concentration of malls in the world…as a result, the mall plays a unique and all-encompassing role in the daily Hong Kong life.”[4] Utilizing their Be Water calling card, protestors would swarm into malls, often breaking out into chants and song. One such song, “Glory to Hong Kong,” became an anthem of the movement. Composed locally, the hymn reverberated in all corners of the city. Inside the shopping mall particularly, Dapiran observed, “how much more that sonority echoed, how much more physically it was felt, in the glass and marble atrium.”[5]

Dapiran provides a riveting recollection of the November 2019 Siege of PolyU, one of the most prominent moments of the movement. After months of conflict, thousands of protestors streamed into the campus of Hong Kong Polytechnic University. They occupied the grounds and used the campus’s elevated position to blockade an important cross-harbor tunnel entrance connecting Kowloon Peninsula to Hong Kong Island. Dapiran describes the university’s dramatic transformation. “Supplies and equipment were strewn everywhere, the walls covered in protest graffiti. The main courtyard was a hive of activity as protestors shifted barricades and prepared equipment.”[6] Rather than storm the campus, Hong Kong Police instead set an encircling siege perimeter, waiting out and arresting the protestors as their food and supplies slowly dwindled. Epic clashes ensued as protestors hurled bricks and petrol bombs while police fired tear gas and rubber bullets. The carnage continued for twelve days, resulting in over 1,100 arrests.

Yet, the people of Hong Kong remained resolute. Just one week later, the city district council held elections. A recording breaking 2.9 million citizens cast their votes, granting pro-democracy candidates a staggering 385 seats versus just 59 for Pro-Beijing contenders. Though not previously controlling any of Hong Kong’s eighteen districts, Pan-democrats secured majorities in an astonishing seventeen. This shattered Beijing’s perpetuated myth that a silent majority of Hong Kongers opposed the movement. As Dapiran states, “The results were unequivocal: a clear majority of Hong Kongers—despite the violence, vandalism, and disruptions of recent months—had supported the protest movement.”[7] The city had spoken, and Hong Kong’s quest for liberties persisted.

One of the greatest strengths of the book is Dapiran’s ability to bring the narrative to life. As a long-time Hong Kong resident, Dapiran does more than observe the protests; he lives through them. He skillfully navigates the complicated political situation, humanizing both sides and illustrating that no situation is black and white. The book immerses the readers into the on-the-ground emotions, fears, and aspirations of the many parties involved. City on Fire was published in March 2020, prior to the July implementation of a draconian new Hong Kong National Security Law. Regardless of the government’s attempts to thwart the movement, Hong Kongers have continued to “Be Water,” constantly switching their tactics and operations to ensure their voices will be heard. As the book concludes, Dapiran contends, no matter the prospects of this current social movement, a new Hong Kong identity has been born. “These are the seeds that will be carried within the Hong Kong people across the coming months, and the coming years, to the next protest movement, and the next.”[8]

[1] Antony Dapiran, City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong (London: Scribe Publications, 2020), 298.

[2] Wong Tsui-kai, “Hong Kong protests: What are the ‘five demands’? What do protesters want?” South China Morning Post, Aug 20, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/yp/discover/news/hong-kong/article/3065950/hong-kong-protests-what-are-five-demands-what-do.

[3] Daprian, Fire, 71.

[4] Daprian, Fire, 117-118.

[5] Daprian, Fire, 213.

[6] Daprian, Fire, 251.

[7] Daprian, Fire, 273.

[8] Daprian, Fire, 289-299.