As news of Iran centers on the Gaza conflict’s spillover, and news regarding Pakistan revolves around its ongoing strikes against TTP militants on their Afghan border, the tit-for-tat strikes on January 16, 2024, and brief tension between Iran & Pakistan over Balochistan seem to have receded as the two countries celebrated the anniversary of their bilateral ties on Monday, February 12, 2024 [1]. This followed the formal resolution of bilateral ties and expansion of security cooperation between Iran and Pakistan on January 29, 2024, putting on display how within fourteen days the neighbors had de-escalated tensions and had even invited ambassadors and foreign ministers for a formal reconciliation [2]. In a surprising turn of events, this episode has provided additional evidence to the extant scholarly literature that transnational militancy between the Iran-Pakistan dyad encourages long-term positive interstate cooperation [3].

While many analysts and commentators were quick to outline Iran and Pakistan’s calculus, few have touched upon border histories and how the Iranian posture underwent a change towards Pakistan following its decisive defeat and independence of Bangladesh in 1971, resulting in a power differential between the two states [4]. The quick reconciliation and the Iran-Pakistan relationship’s ability to cherish bilateral relations largely on Iran’s terms over addressing root causes of disenfranchisement of their Baloch minority’s livelihoods points to a clear leverage an expansionist Iran retains over its nuclear-armed neighbor. The growing strategic importance of Iran’s Chabahar port initially with India and recently with Afghanistan after their $35 million dollar port deal inked on March 9, 2024, has also raised concerns for Islamabad after their decision to retaliate against TTP militants a week later [5][6]. Iran’s security and economic accords with India coupled with Pakistan’s deep ties with Saudi Arabia further complicates their bilateral relationship, making it impossible to view their dynamic independently of Indian and Saudi variables [7].

In his seminal work, Pakistan’s Foreign Policy, Shahid Amin from his forty-year experience in diplomacy notes that the erstwhile Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi who ruled from 1941 to his ousting in 1979, originally welcomed Pakistan as a non-Arab Muslim country and a counterweight against both the Arab World and the Soviet Union[8]. Given Pakistan’s inception in 1947 and its dismemberment in 1971 happened within the Shah’s reign, Amin recounts the Shah’s massive shift in attitude and geo-strategic posturing toward Pakistan which henceforth assumed the role of “senior partner” after 1971 [9]. Although Iran supported Pakistan in the first two wars against India and was the premier lifeline for military supplies during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, the Shah openly suggested annexing Balochistan on Iran’s eastern border in “case of further dismemberment” [10].

Even after the Islamic Republic of Iran replaced the Shah’s regime, Pakistan’s strongly pro-U.S. Cold War affiliations through pacts—such as the Baghdad/CENTO Pact (1955), and SEATO (1954)—, despite their mutual interest in Afghanistan, has allowed Iran to grow influence by deepening relations with India and portraying Saudi Arabia and Gulf states as separatist backers of Balochis or Pashtuns, while themselves deploying non-state actors from Pakistan’s Shia minority. While Pakistan’s 33rd Foreign Minister Abbas Jillani lauded their brotherly ties at the January 29, 2024, resolution meeting, Iran was able to confirm Pakistan’s narrative of a “third country factor” being at play, which instead implicates India as the instigator of the initial January 16th strike with historical ties to the India-backed Baloch Liberation Army [11][12].

Ultimately, pinpointing how Iran gained a superior posture over Pakistan and why the Baloch people’s decades-long quest for independence has failed at the hands of both Pakistan and Iran’s security forces with strings attached to commercial interests in Washington and Beijing, can help paint a better picture of how to address the root causes of state repression, apartheid and security competition in Balochistan. As the British historian, Selig Harrison, noted in his observations of Southwest Asia, Balochistan comprised a land mass bigger than France, strategically located with command of over 900 miles of Arabian coastline, making it a potential focal point for superpower conflict [13].

Iran’s Wild West and Pakistan’s Most Militarized Zone

Balochistan as a region in Central Asia is split between Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, with over 90% residing within Iran’s Sistan-Balochistan province or Pakistan’s Balochistan province [14]. Despite accounting for 42% of Pakistan’s landmass, the Baloch people account for only 3% of the population [15]. While the first expressions of Baloch nationalism can be traced back to 1666, it was not until the Khan of Qalat conceded to British victory in 1877 that Balochistan became a province of erstwhile British India [16]. The Baloch people have two linguistic divisions between those who speak Brahui and Baloch. This linguistic divide among Balochis is compounded by their tribal differences as over eighteen tribes reside in Balochistan, with the Marris, Bugtis and Mengals being the most prominent for uniting the many groups based on solidarity to outside threats [17].

Scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot have attested their sparsely populated region to the Pakistani state’s failure to provide education, employment, and security to the Baloch people, whose land’s rich natural and mineral resources have been diverted to Punjab [18]. Additionally, the four wars for Balochistan, the ongoing legacy of disappearances of Baloch people and leaders in addition to their massive migrations to either other provinces or the Gulf in search of employment, have led to the Baloch people being underrepresented in every facet of Pakistani public life [19]. By 1980, the literacy rate in Balochistan was 11% and the region boasted only one Baloch graduate in the 70s. Today, out of the 200 corporations in Pakistan, none are headed by Balochis, nor have there been any Balochi Pakistani Ambassadors with only 506 Balochis serving in the Pakistan Army [20].

Similarly, in Iran, scholars like Arash Azizi mention how Iran’s eastern border with Pakistan and Afghanistan has long been regarded by everyday Iranians as the “Wild West” [21]. In Azizi’s narration of Qasem Soleimani’s life, Soleimani himself was born and raised near the Sistan-Balochistan region in his hometown of Kerman, where as a boy he was wary not to pick fights with peers from local tribes out of fear to instigate a family feud [22]. The Shah’s approach to Balochistan was initially to appease their population by extending economic aid to both Iran and Pakistan-controlled Baloch territories.

However, the post-1971 climate in Pakistani Balochistan reflected the same mistakes the Pakistani state made in Bangladesh by imposing their same centralizing reflex over the Baloch [23]. According to Jaffrelot, the central government continues to disapprove of a spoils system that would deprive the traditionally Punjabi national elite of their positions in the bureaucracy, which in turn fuels the Baloch grievances of internal colonialism and attacks on Punjabis living in Balochistan. In August 2010, a bus bombing killed over 250 non-Balochis which led to a departure of over 100,000 Punjabis, which Baloch militants claim was in response to the Pakistan Army’s kill-and-dump operations in 2009 [24]. This cycle of violence in Balochistan is rooted in Pakistan’s unsettled national integration as a result of centralist policies demonstrated first in Bangladesh during 1971, where the military establishment and the Punjabi elite in general leverage violent forms of repression to concentrate power whether it be civilian or military.

Pakistan Inherits British Afghan Policy of Strategic Depth

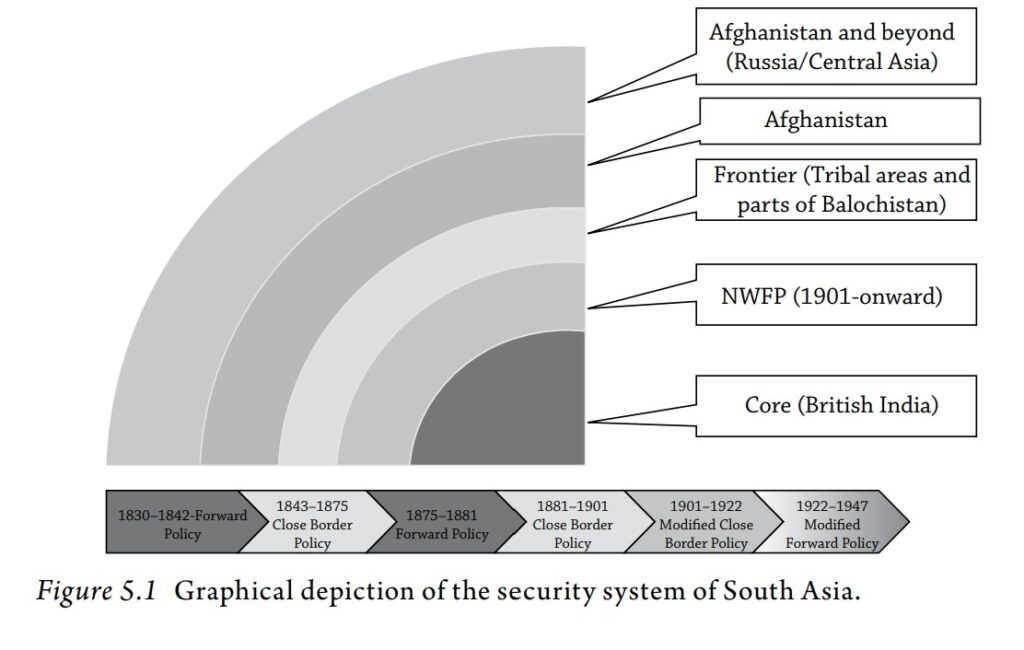

Since Partition, a consensus among policymakers and scholars focused on South Asia is that, unlike India, Pakistan inherited British India’s policy of strategic depth, referring to the need of having a security buffer on its border with its Afghan and Central Asian neighbors [25]. Given that Afghanistan’s leadership under every regime since Partition has rejected their Durand Line marking their post-colonial border with newly independent Pakistan as a British-imposed and thus defunct security buffer [26]. As a result, the new Pakistani leadership has made every effort to secure their interests on the Western front where they face an ideological threat while facing a hegemonic neighbor in the East with their traditional rival—India.

Figure from Fair, C. Christine. Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War. Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 2014.

According to Christine Fair, Pakistan followed the British model for Afghan policy by assuming their role in the South Asia security model [27]. The Durand line served as a 1,519-mile border from the southern tip of Balochistan to the Wakhan corridor in order to prevent confrontation between the British and Czarist Russia. As a result, the British South Asia security system deemed British India the core, but the Northwest Province and Balochistan as the periphery of the empire [28]. Fair argues that as a result, notions of citizenship varied across this space as Punjabis and Sindhis were subjects of British India, but Balochis and Pashtuns were beholden to different legal regimes of British India driving away their sense of belonging in Pakistan today [29].

Following Partition, India as well as Iran and Afghanistan have all laid claim to Pakistan’s territories which Islamabad has adopted and maintained through the British-inherited policy of strategic depth. The arrest of RAW agent Kulbushan Yadav in Gwadar port in 2017 with a fake Muslim name and passport, and Baathist Iraq’s foiled attempt to arm the Baloch Liberation Front in 1973, put on display the interests of neighboring states hoping to exploit the centrifugal tendencies of Pakistan’s ethnic minorities [30]. Fair further points out how the Pakistani state repeats the same mistake of 1971 by suppressing minorities even though the difficulty of integrating all their ethnic groups into the nationalist project of Pakistan is clear [31].

Despite all the internal security challenges, India ranks first among regional competitors. To explain, Stephen Cohen provides three models by which hawks in India have hypothesized their final defeat of Pakistan: (1) luring Pakistan into a military confrontation to bring about a final triumph over the Pakistan Army, (2) pushing for increased support for separatist forces in Sindh, NWFP, and Balochistan leading to civil war and (3) allowing India’s greater economic potential to dominate Pakistan and deem it a failed state [32]. The second scenario—the 1971 model—has been pursued by Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan to this date with Soviet support in all three. However, all three scenarios involve an Indian hand and have precedents in the mind of Islamabad’s military establishment.

Pakistan’s failure to properly integrate its ethnic groups into its nationalist project has allowed Iran to take an active interest on behalf of Pakistan’s Shia population [33]. Iran’s mantle as the “protector of the Shia,” in addition to its ever-growing network of proxy groups on its Eastern border has shown why groups like Jaish al-Adl, have proven themselves as threats to Islamabad’s national security [34]. Iran’s proxy network in Pakistan is further compounded by the strategic decision to grow closer with India as part of Iran’s “Look East” policy starting in 1994 [35]. Since then, a strategic partnership, the Russo-Iranian-Indian transport corridor, was declared in 2003, and India actively engaged with Iran through the Chabahar port as an alternative route to Afghanistan and Central Asia to compete with Pakistan [36]. In response, Iran alleges that Pakistan-based Jundallah executes terror attacks in Iran from sanctuaries in Pakistan. The Cold War between Iran and Saudi Arabia following the 1979 revolution also partly influenced the security competition as Qasem Soleimani even warned Pakistan on February 19, 2019, that Saudi Arabia was pumping money into Pakistan by pitting it against its neighbors during the 2019 Pulwama incident [37]. Similarly, Iran’s post-revolution leadership applies rhetoric in their counterterrorism strategy to implicate a Saudi hand in Balochistan’s terrorism problem by constructing a notion that a joint Islamic State/Wahhabi/Salafist sectarian dimension is working against Iranian interests in efforts to pressure Pakistan [38].

China as a Mediator and the Emerging Saudi-India Factor in Central Asia

The most significant recent episode that brought Pakistan and Iran to the table over cross-border militancy in Balochistan was in 2014, when Iranian border guards killed a Pakistan Frontier Corps Guard within Pakistan after seizing a border town for six hours [39]. Both countries exchanged mortar shelling shortly afterwards, where Iran fired 42 rockets into Pakistan which injured 7 civilians in pursuit of suspected Baloch militants. Between 2003 and 2016, anti-Iran, Sunni, Baloch militant groups like Jundollah, Jaish-Ul-Adl and Harekat-e-Ansar-e-Iran conducted nearly 15 significant attacks, killing over 200 people and injuring hundreds [40]. On March 14, 2014, the Iranians proposed to their Pakistani counterparts to allow them the ability to maintain security on their joint border after the repeated occurrences made evident that Pakistanis were not providing adequate security. Journalist Umar Farooq reported that Iranian border forces freely roam the joint border, while Iran’s then-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Javad Zarif, stated in March 2014 that Pakistan was not Iran’s biggest problem related to transnational violence [41].

Associate Research Fellow at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Abdul Basit, lists six factors responsible for the positive impact of bringing Iran-Pakistan relations closer: security priorities, third-party relations, timing, economic potential, internal signaling and exhaustibility of other options [42]. Not only can neither Iran nor Pakistan afford an interstate war, but their respective burning security rivalries with Saudi Arabia and India accounting for the third-party connections and common economic interests draw them towards increasing bilateral cooperation. This was made particularly clear after 2014’s heightened security cooperation at Iran’s request and the Pakistan Army naming domestic violent non-state actors as a greater threat to national security than their arch-rival India in 2013 [43].

Pakistan’s security fixation with India coupled with Iran’s endemic rivalry with Saudi Arabia are recurring themes for which Buzan and Weaver’s model of regional security complex theory (RSCT) provides a robust explanation for the Iran-Pakistan security evolution [44]. While the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Pakistan Army are the real stakeholders on matters of national security and foreign policy decision-making for Iran and Pakistan, both countries have failed to develop a mechanism to address bilateral tensions due to their respective establishments repeatedly finding blame in third-party involvement [45]. Iran offering a gateway to Central Asia for India via the Chabahar port in Iran and the Zaranj-Delaram road between Afghanistan and India is considered to have formally introduced the India factor in Pakistan-Iran relations [46]. Although Pakistan’s strict neutrality over Yemen weakened the perceptions of security dependence on Saudi Arabia, the Iranian post-revolution leadership’s rhetoric about their Sunni-led efforts to destabilize Iran from within, particularly with their most porous border in Sistan-Balochistan, poses serious concerns.

A significant development in the strikes between Iran and Pakistan this time as opposed to the prior 2014 episode, was the advanced notice as well as the mediation facilitated by Beijing [47]. Balochistan is the site of China’s most ambitious and expensive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) initiative in South Asia — the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), where the flagship Gwadar port has been a target of attacks on Chinese personnel and expats [48]. On a deeper level, Pakistan cherishes its close ties with China as its “Iron Brother,” relying on Beijing on a range of issues from defense, as a top customer of Chinese weapons, to economic investment and balancing India—a mutual adversary for both China and Pakistan [49]. Beijing has ambitious plans for Pakistan to play a central role in its economic plans for South Asia as a maritime, continental transportation and trading hub. CPEC serves as a bridge between Beijing and the Arabian Sea, intended to build stronger trade networks with the Middle East [50].

China has long invested in projecting influence in Central and South Asia, and as a close partner to both Iran and Pakistan, Beijing cannot afford to have its commercial interests harmed by security threats. With tens of billions of dollars invested in both countries, the Chinese Foreign Ministry immediately pledged that Beijing would “play a constructive role in cooling down the situation” immediately after the tit-for-tat missile exchange [51]. China is also both Iran’s primary buyer of sanctioned oil and a signatory for a 25-year economic and security agreement inked in 2021 [52].

Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute, notes how Pakistan and Iran “had enough in their relationship to ease tensions themselves,” suggesting China merely provided a forum to assure mutual interstate cooperation [53]. Additionally, Abdul Basit argues that given China’s massive investment and strategic cooperation with both countries, “the stakes are high and they really can’t afford for things to get any worse between Iran and Pakistan [54].”

The U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific similarly cannot allow a front to open between Iran and Pakistan, given their hands being tied with Iranian proxies on its border with Israel and the Red Sea. For this reason, the U.S. has allowed Iran and Pakistan to serve as conduits for its interests in balancing the Soviet Union during the Cold War, but with a revisionist Iranian regime, the need to contain a potential Iranian front in the Indo-Pacific will bear extraordinary costs.

Following the floods in 2022, the U.S. stepped up to provide substantial funds and development assistance in heavily hit Balochistan [55]. To Washington, Balochistan has been a topic of limited concern since the days of Nixon and Kissinger, of whom the former once claimed to not regard “the Balochistan problem if it hit him in the face [56].” However, India’s espionage activities in Gwadar and New Delhi’s larger overture towards Iran for economic and strategic cooperation potentially allows the U.S. a window of opportunity to play New Delhi’s interests against Beijing’s ambitions of securing CPEC.

Conclusion

The new consensus in Central Asia among analysts and scholars is that India and China’s growing influence through economic statecraft has played a major role in the posture of states in this region. Pakistan’s own failure to consolidate their internal security by continually repressing minorities had also allowed Iran to gain the upper hand, with India as an asset and China as a mediator in case of escalation.

Balochistan has proven Selig Harrison’s prediction of becoming a focal point for superpower conflict as Iran has demonstrated superior leverage over Pakistan, turning the tables on Islamabad, while also securing backing from Beijing and New Delhi who seek to deepen their influence in the region. While Pakistan still manages to hold its leverage in matters as a nuclear state capable and willing to impose costs on neighboring Afghanistan or Iran through retaliatory strikes, Islamabad no longer holds a superior posture in Central Asia due to Iran’s ascent despite remaining as a nuclear threshold state.

With U.S. regional interests firmly fixated on the conflict in Gaza, Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea and the PLA’s gray-zone aggression in the South China Sea, Beijing was able to mediate this instance of Iran-Pakistan border tensions rather quickly [52]. In line with scholarly insights about transnational border militancy actually incentivizing bilateral cooperation between Iran and Pakistan and the India-Saudi third-party connections still leaving suspicion between the two neighbors, Balochistan as a hotspot will remain a potential sight for escalation. While the 2014 tit-for-tat strikes made clear Iran had more leverage and legroom after Pakistan complied with their request to police the border within Pakistani territory, this most recent 2024 tit-for-tat strike brought a reconciliation within only two weeks under the authority of Beijing. Both countries seem to simply have their hands full with more pressing security concerns, but their eyes remain fixed on third-party movements whether it be espionage, infrastructure projects or minority mobilization.

Endnotes

- Alexandra Sharp, “Iran Fortifies Ties with Pakistan to Combat Terrorism,” Foreign Policy, January 29, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/29/iran-pakistan-ties-executions-israel-espionage-drone-strike-jordan/.

- Ibid.

- Saira Basit, “Explaining the Impact of Militancy on Iran-Pakistan relations,” Small Wars & Insurgencies, 29:5-6, 1040.

- Shahid Amin, “Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: A Reappraisal” (London: Oxford University Press, 2021), pg. 99.

- Reuters Staff, “India inks 10-year deal to operate Iran’s Chabahar port,” Reuters, May 13, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-sign-10-year-pact-with-iran-chabahar-port-management-et-reports-2024-05-13/.

- Atlantic Council experts, “Experts react: Pakistan just carried out airstrikes on Afghanistan. What’s next?” Atlantic Council, March 18, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/experts-react-pakistan-just-carried-out-airstrikes-on-afghanistan-whats-next/.

- Umer Karim, “The Pakistan-Iran Relationship and the Changing Nature of Regional and Domestic Security & Strategic Interests,” Global Discourse, 13:1, 20.

- Shahid Amin, “Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: A Reappraisal” (London: Oxford University Press, 2021), pg. 99.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Abdullah Momand, “No doubt militants in Pak-Iran border areas supported by ‘third countries,’ says Iran FM,” Dawn, January 29, 2024, https://www.dawn.com/news/1809493.

- Iran International staff, “Iranian FM Alleges Third Country Support For Border Militants,” Iran International, January 29, 2024, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202401299558.

- Alex Vatanka, “Iran and Pakistan: Security, Diplomacy and American Influence,” (New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2015), pg. 87.

- Christophe Jaffrelot, “Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience” (London: Oxford University Press, 2015), pg. 136.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, pg. 138.

- Ibid, pg. 141.

- Ibid, pg. 143.

- Ibid.

- Arash Azizi, “The Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the US, and Iran’s Global Ambitions”, (New York: Oneworld Publications, 2020), pg. 124.

- Ibid.

- Christophe Jaffrelot, “Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience”, (London: Oxford University Press, 2015), pg. 149.

- Ibid, pg. 145.

- Christine C. Fair, “Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War”, (London: Oxford University Press, 2014), pg. 112.

- Ibid, 109.

- Ibid, 111.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Shahid Amin, “Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: A Reappraisal” (London: Oxford University Press, 2021), pg. 274.

- Christine C. Fair, “Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War”, (London: Oxford University Press, 2014), pg. 170.

- Stephen Cohen, “The Idea of Pakistan”, (London: Brookings Institution Press, 2006), pg. 78.

- Alex Vatanka, “Iran and Pakistan: Security, Diplomacy and American Influence” (New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2015), pg. 237.

- Ibid.

- Chietigj Bajpaee, “India’s Engagement with the Middle East Reflects New Delhi’s Changing Worldview” War on the Rocks, May 22, 2024, https://warontherocks.com/2024/05/indias-engagement-with-the-middle-east-reflects-new-delhis-changing-worldview/.

- Shahid Amin, “Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: A Reappraisal” (London: Oxford University Press, 2021), pg. 289

- Ibid.

- Saira Basit, “Explaining the Impact of Militancy on Iran-Pakistan relations,” Small Wars & Insurgencies, 29:5-6, 1052.

- Ibid, 1041.

- Ibid, 1042.

- Ibid. 1041.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 1049.

- Umer Karim, “The Pakistan-Iran Relationship and the Changing Nature of Regional and Domestic Security & Strategic Interests,” Global Discourse, 13:1, 24.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 28.

- Alexandra Sharp, “Iran Fortifies Ties with Pakistan to Combat Terrorism,” Foreign Policy, January 29, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/29/iran-pakistan-ties-executions-israel-espionage-drone-strike-jordan/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Umer Karim, “The Pakistan-Iran Relationship and the Changing Nature of Regional and Domestic Security & Strategic Interests” Global Discourse, 13:1, 40.

- Reid Standish, “High Stakes For China Amid Simmering Iran-Pakistan Tensions,” Radio Free Europe, January 22, 2024, https://www.rferl.org/a/china-pakistan-iran-mediating-conflict/32787233.html.

- Reuters staff, “”Iran and China sign 25-year Cooperation Agreement,” Reuters, March 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/iran-china-sign-25-year-cooperation-agreement-2021-03-27/.

- Michael Kugelman, “Tensions Rise on Pakistan’s Borders,” Foreign Policy, January 31, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/31/pakistan-border-tensions-iran-afghanistan-militant-threat/.

- Reuters staff, “Iran and China sign 25-year Cooperation Agreement,” Reuters, March 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/iran-china-sign-25-year-cooperation-agreement-2021-03-27/.

- Reuters staff, “United States pledges further $30 million in aid to flood-hit Pakistan,” Reuters, October 27, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/united-states-pledges-further-30-million-aid-flood-hit-pakistan-2022-10-27/.

- Alex Vatanka, “Iran and Pakistan: Security, Diplomacy and American Influence,” (New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2015), pg. 237.