Deterrence is tired. It has been put to work for more than seventy years in the nuclear warfare domain, and it has performed admirably there. After all, the world is still intact. The problem is not that deterrence does not do its original job well. Rather, it is that the use of deterrence as a strategy has been stretched into areas for which it is not appropriate: lately, the discussion of deterrence’s role in cybersecurity. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) advocates for it,[1] and Smeets proclaims, “Long live cyber deterrence.”[2] However, such enthusiasm may be misplaced. Cyber is fundamentally different from most forms of kinetic warfare, especially nuclear. Consequently, it requires a strategy more suited to its short-lived, limited impact nature.

Interestingly, Smeets, the champion of cyber deterrence, also indicates the strategy’s shortcomings, observing that “cyberweapons … have a short-lived or temporary ability to effectively cause harm.”[3] The transitory nature of the damage from cyber attacks suggests an ability to absorb the impact. Of course, prevention is important and should be pursued whenever possible, but when adversaries breach defenses, the path to recovery tends to be more manageable when compared to kinetic warfare. As a result, unlike nuclear warfare, there is less need to prevent a first strike at all costs, and it is certainly true that “[w[hoever shoots first dies second.”[4]

Because cybersecurity rarely has an absolute need for prevention, cybersecurity strategy can include a retrospective component, where efficiency in post-attack remediation is fundamental to addressing the threat. Cyber insurance becomes an important economic security component to cybersecurity strategy, in that the flow of high-velocity capital after a cyber attack could accelerate the recovery process, increasing resilience and dulling the nature of the threat itself. To contribute more effectively to this form of economic and cyber resilience, though, the cyber insurance market will need to continue to mature. Currently, it suffers from a shortage of capital relative to near-term demand, let alone the risk as a whole.[5]

Additional capital could come from the global insurance linked securities (ILS) community, a corner of the insurance market that has engaged little with cyber risk and whose lack of engagement has generally been misunderstood by insurance and international relations scholars. The ability to access that market, which represents more than $100 billion in assets under management (AuM), could provide the capital needed to help bolster the cyber insurance sector and make it a more meaningful contributor to cybersecurity strategy, allowing deterrence the rest it deserves.

Breaking the Deterrence Overreliance

Deterrence no longer fulfills the needs of cybersecurity strategy. It is best left to truly existential risks where the first strike could trigger a chain reaction that ultimately leads to “mutually assured destruction,” a scenario in which there are, by definition, no winners. Lewis and Painter offer an excellent description of deterrence in relation to cybersecurity in their podcast, Inside Cyber Diplomacy: “I love ideas from the 1950s … deterrence is the ‘Ozzie and Harriet’ of cyber security.”[6] Gray is similarly blunt, referring to doctoral students looking at the subject: “[I]f only it were 1952 or 1953, they could make their name with a pioneering study of deterrence.”[7] Seventy years later, cybersecurity needs a strategy relevant to the threat.

Ultimately, deterrence is most effective when the magnitude of the consequences of its failure are unacceptable. That context makes it easier for the parties involved in deterrence to achieve the fundamental agreement on which deterrence relies. As Gray comments, deterrence works only when one “decides that it is deterred.”[8] As the consequences of an attack become more manageable, that sort of agreement becomes more difficult to achieve. The transitory nature of cybersecurity threats, noted by Smeets above, speaks to the reduced consequences from this attack type and thus an increased likelihood that the impact of an attack could be absorbed.

The shortcomings of deterrence for cybersecurity are most evident with a direct comparison, using two attacks on energy targets over the past year. The first, Colonial Pipeline, was a ransomware attack that led to the cessation of operations. The other incident, more recently, destroyed windfarm equipment in Ukraine during the conflict this year. The former was up and running in only five days, with insured losses (as a proxy for economic impact) amounting to only $10 million, according to PCS internal research.[9] The windfarms in Ukraine, on the other hand, may see aggregate insured losses exceed $800 million and take months—or even years—to recover.[10]

The difference between the pipeline and the windfarms suggests that deterrence no longer suffices. The inevitability of cyber attacks and the demonstrated ability to recover from them relatively quickly makes clear that the more effective strategy is to invest in preventive measures where possible and develop the capabilities to respond to such attacks and facilitate recovery as quickly and cost-effectively as possible. An economic solution makes far more sense than an ongoing escalation of offensive capabilities. This only works, though, with sufficient capital available to finance economic security capabilities.

Constraints on Capital and Security

The use of insurance as a lever in economic security is hardly original; it has been employed for centuries as a way to help individuals and business recover from unexpected loss through the transfer of risk from one party to another in exchange for a fee (i.e., insurance premium).[11] Insurance has contributed to economic growth by providing protection directly and “through complementaries with the banking sector and the stock market.”[12] This thinking extends to the cyber domain, as well.

Unfortunately, the cyber insurance industry[13] has been unable to address demand for protection, which leaves a segment of society exposed to cyber risk. Despite seeing significant year-over-year growth in premium, from an estimated $5.5 billion a year ago, according to internal estimates by PCS (the team this author leads at data/analytics firm Verisk), to as high as $9.2 billion.[14] However, protection provided has not grown with the premium charged for it. The increasing threat from ransomware over the past few years has led to higher premiums on less protection, suggesting that while the cost of protection is growing, the amount of protection available is not.

Reinsurance, commonly known as “insurance for insurance companies,” has become crucial to the growth of the cyber insurance sector over the past few years,[15] although the need for reinsurance support was identified as far back as 2014 by Biener, Eling, and Wirfs, who observe, “The development of a viable cyber market could thus benefit from increasing reinsurance capacity for the risks.”[16] Since then, reinsurance has become a primary driver of cyber insurance growth, swelling from $2.5 billion in 2020 to approximately $3 billion today, according to internal PCS estimates. However, reinsurers have not allocated enough additional capital to meet the needs of insurers, which has limited how much cyber insurance they can underwrite. Essentially, the sector has run out of capital.

ILS has often been raised as a potential solution to the capacity constraints experienced across the re/insurance industry, but rarely with any examinations of the conditions that have prevented for so long the connection of the ILS and cyber re/insurance markets. The prospect that “peak cyber risks will be … transferred to the capital markets” remains a possibility, according to Carter, Pain, and Enoizi, who claim there are “few, if any, transactions, at least in the public domain.”[17] However, there has been no review of the extent to which ILS funds participate in the cyber insurance market, and what has impeded their further adoption of this form of risk. The absence of information on ILS attitudes toward and appetites for cyber risk leaves a gap not just in the global insurance industry but also in cybersecurity strategy. With cyber threats more transitory than their kinetic counterparts, strategies like deterrence must give way to economic security levers that better suit the risk.

ILS market cyber survey and findings

The global ILS market consists of more than forty ILS fund managers around the world, with aggregate AuM of just over $107 billion (all figures in US dollars).[18] The majority of that AuM, though, sits with the twenty-five ILS funds that have at least $1 billion in AuM. Approximately 80 percent of the worlds ILS funds are in Bermuda (the most), United States, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom—where all respondents to this survey are located. Historically focused on property-catastrophe risk,[19] ILS funds have branched out on a limited basis into more forms of risk, including specialty classes like marine and energy, political violence, property per risk, and aviation. Some have also engaged in casualty lines of business.[20] While the future of cyber ILS has been difficult to determine, some have identified it as a potential ILS growth driver.[21]

Cyber has generally been difficult to place in the ILS market,[22] although it has been done before.[23] Popular perceptions have focused on the reported small size and infrequency of the transactions completed, as well as the fact that so few have made it into the public domain.[24] As a result, misconceptions about the ILS market and its appetite for cyber re/insurance risk appear prevalent. To address this development, the first study of its kind was conducted, with representatives from twenty-four ILS funds[25] interviewed, representing 78 percent of the ILS market by AuM.[26]

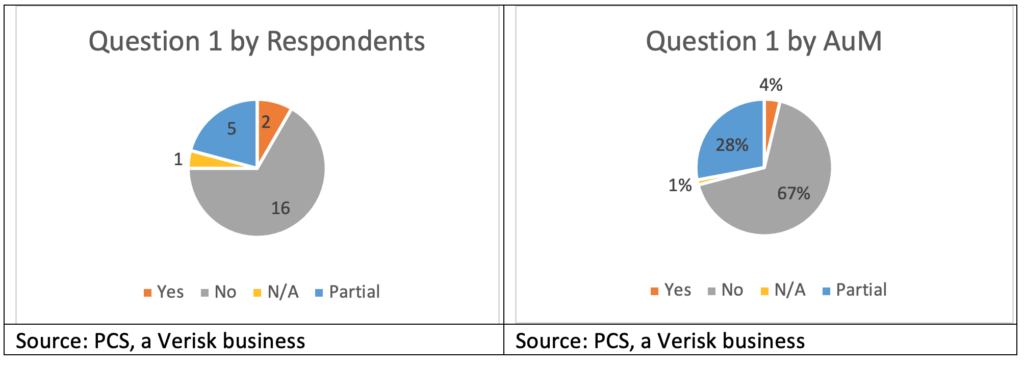

Question 1: Do you have a mandate preventing you from trading cyber?[27]

A persistent and common misconception in the traditional re/insurance market is that ILS fund mandates prohibit them from participating in cyber, along with many other man-made classes of business. While ILS fund manager appetites for cyber re/insurance risk may vary, most are not prohibited specifically by mandate. In fact, 95 percent of respondents by AuM (22 of 24 respondents) are not prohibited from engaging in cyber re/insurance transactions by mandate, although 28 percent do have partial prohibitions (5 respondents).

Of the two respondents with prohibitions on assuming cyber re/insurance risk, one has remained firm and emphasized that it has no interest in or appetite for such risk. The other reported it has been more willing to explore cyber, to include revisiting the issue with its end-investors, with the thought that a favorable market could be a reason to revisit existing mandates. That ILS fund manager subsequently decided to stay away from cyber, at least for the time being. Several funds explained that they have no appetite for cyber re/insurance risk, even though trading in that class of business is not specifically prohibited by their mandates. They noted that their mandates are sufficiently broad to allow them certain flexibility beyond property-catastrophe risk, and that they may choose not to assume cyber risk for a variety of other reasons, ranging from price and structure to portfolio construction philosophy.

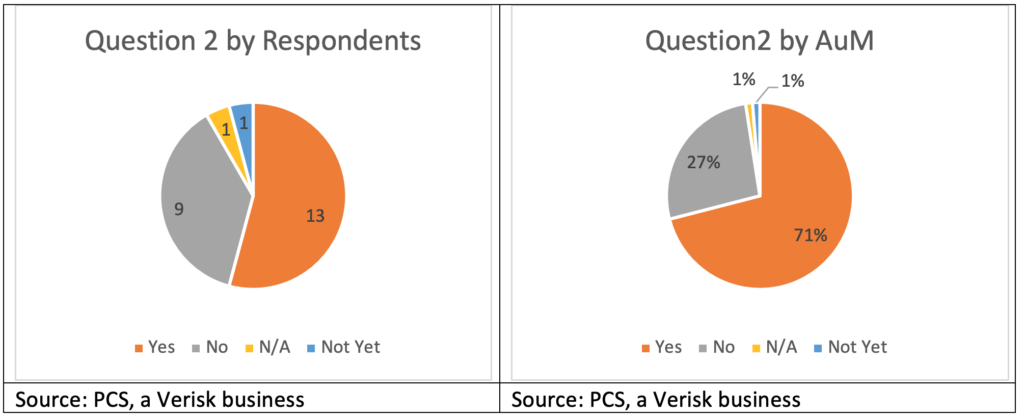

Question 2: Are you interested in trading cyber?

Thirteen respondents (71 percent by AuM) are interested in cyber re/insurance risk, although timeframes vary. One respondent indicated “not yet,” but the sentiment was shared by several others who indicated that they may enter the market when they feel the time is right, or when enough of their peers have, such that they either feel comfortable or simply that they cannot avoid the cyber re/insurance market any longer. One large ILS fund (in the top five by AuM) responded that it was not “desperate” to get into cyber re/insurance but remained interested in seeing opportunities and would enter when a transaction met their standards. Another got quite close, but specific terms prevented the transaction from being completed.

Of the respondents interested in consuming cyber re/insurance risk, some reported they have already done so, and are either committed to the class of business or are showing further appetite for cyber risk, which has gone unmet due to lack of deal flow. Some have traded cyber in prior roles and are interested in doing so again, when conditions inside and outside their organizations are appropriate. Among the eager, some technical barriers do remain, such as the potential for cyber correlation with broader financial markets, a sentiment not universally shared, and whether a dedicated portfolio would be appropriate (versus inclusion in a property-catastrophe-focused portfolio).

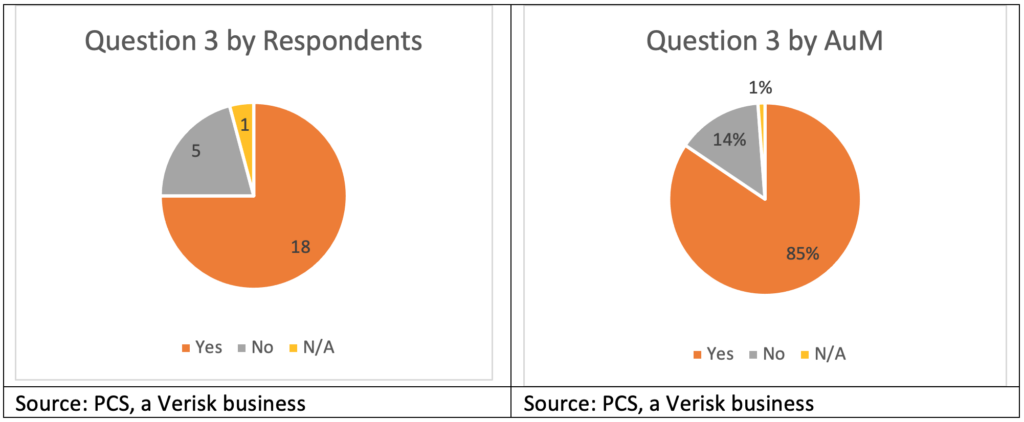

Question 3: Have you analyzed/reviewed the cyber market?

While eight respondents, per above, indicated that they are not interested in trading cyber re/insurance, it is not because they have taken that position ignorantly. The overwhelming majority of respondents—in both number (18) and AuM (85 percent)—indicated that they have reviewed the cyber re/insurance market. The ILS sector knows there is enormous demand for cyber insurance, which translates to further demand for reinsurance and retrocession, suggesting that eventually, the market will have to engage. In fact, several respondents offered a sense of fatalism in this regard, understanding that, eventually, they would have to assume cyber risk simply to be a part of the market.

Of the five companies responding that they have not reviewed the market, three are small (less than $1 billion in AuM) and have indicated that they are not interested in cyber re/insurance under any circumstances, a sentiment that of course could change some day based on market dynamics and perspective. One of the larger respondents believes that a thorough and meaningful review would require a significant effort and that investment is not warranted given that they are not interested in entering the sector yet.

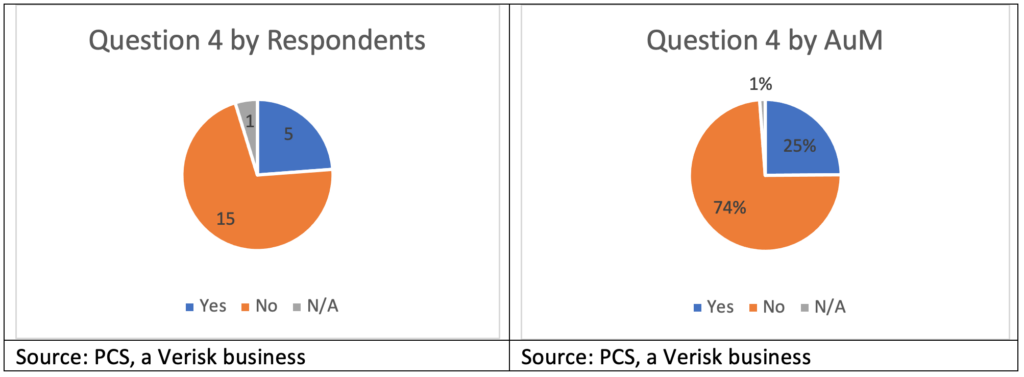

Question 4: Have you traded cyber?

Cyber re/insurance engagement with the ILS market has been fairly frequent, although the trades have tended to be small. Five respondents, representing $21 billion in AuM have traded cyber re/insurance, representing 25 percent of the ILS community by AuM. While cyber re/insurance trading activity still lags that of other specialty lines of business considerably—such as marine and energy, terror, aviation, and property per risk—the fact that more than a quarter of the sector has experience with cyber suggests a foundation for further market growth over the coming years.

Reasons for cyber reinsurance appetite varies, as well. In some cases, ILS fund managers said they see the potential for the diversifying benefits of cyber relative to an existing property-catastrophe portfolio, although this relates specifically to a fund manager’s strategy, the types of capacity available, and the interests of its end investors. While some indicated being open to diversification within an ILS allocation, others responded that their end investors see ILS as the diversifier and do not want that diluted by non-catastrophe investments or do not want the additional overall correlation brought back into their own portfolios.

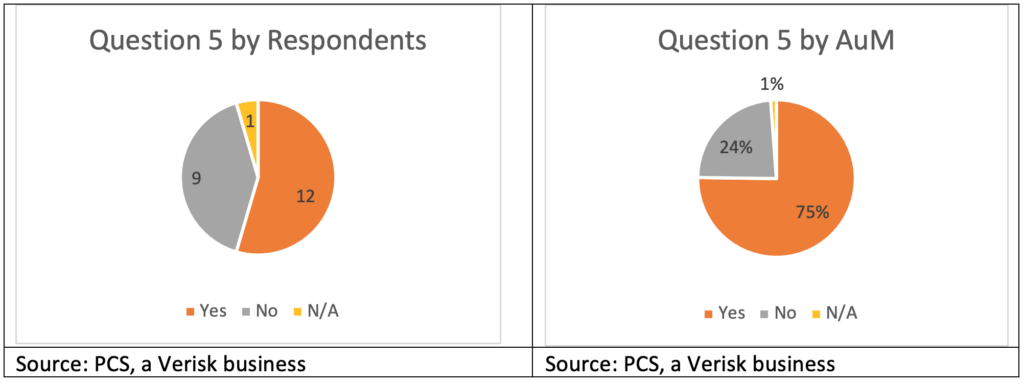

Question 5: Have you been shown cyber trades?

Twelve respondents, including most of the top ten by AuM, were shown cyber reinsurance deals by reinsurance brokers. Some have been reviewing such opportunities for several years and still have no plans to enter the sector. Those funds indicated understanding that they will eventually have to take a serious look at the cyber reinsurance market, particularly if today’s structural challenges can be overcome and the market is able to return to the rapid growth it enjoyed a few years ago.

Other reported reasons for taking a look at cyber reinsurance deals (particularly for ILS funds not yet engaged in cyber reinsurance) include curiosity, using submissions as a way to learn more about the market, and finally looking for the sort of transaction that a fund might consider for first entry. A small subset of respondents has seen an increasing number of transactions every year because they are actively looking for an entry point, with the distinct possibility that it will come in 2022. The fact that market conditions did not lead to more aggressive pursuit of the other nine respondents (and any other ILS funds historically not interested in cyber re/insurance) results from several factors. Many respondents who were not shown cyber re/insurance deals figure that reinsurance brokers knew that, for them, there were no circumstances under which such transactions would be considered. Additionally, the nine respondents who were not shown any cyber reinsurance submissions over the past year represent only 24 percent of the respondent base by AuM, and smaller ILS funds may struggle disproportionately to take even small lines on cyber reinsurance programs.

Conclusion

Sound a death knell for deterrence in the cyber domain. Its time has passed. There is no need for a procession, because as Lonsdale so aptly observes, a “May Day parade of malware” would not be terribly inspiring (2018 417). Instead of focusing on prevention at all costs, cybersecurity may benefit from splitting “all costs” into prevention and reconstruction, with the latter brought into the process to address the inevitability of cyber attacks and a recognition that fast recovery can support economic stability and security. The role of insurance in financing post-event response is well established and expanding it to the cyber domain is both intuitive and demonstrably useful. For insurance to become a more important component in this new approach to cybersecurity, though, it will have to grow significantly.

The shortage of capital from which many in the cyber insurance market currently suffer could be resolved through the engagement of new sources, particularly the ILS sector. The belief that the ILS market had little interest in cyber risk resulted directly from a lack of discussion with the ILS community. Quite simply, nobody asked about their appetite for cyber risk. This study shows that, contrary to prevailing opinion, the ILS market is quite ready to consume more cyber insurance risk, which could help the sector grow and play a more important role in societal stability and economic security. Further, even among those with no current appetite for cyber risk, there seems to be a certain fatalism that, at some point, they cannot afford to avoid this segment of the market. The question now is not whether there is capital support for cyber insurance from ILS; rather, it is a matter of how this new source of capital can be engaged most effectively.

Some work remains, of course. However, the current impediments to the flow of ILS capital into the cyber insurance sector are manageable, as evidenced by the fact that five respondents have already engaged in cyber transactions. Progress toward mutually agreeable pricing between buyers and sellers along with deal structure is attainable. From twelve months of this writing, the amount of cyber ILS transactions completed is likely to increase substantially from today’s levels, if for no other reason than the combination of acute protection buyer need and the increased interest among ILS funds in providing such cover.

Long live cyber deterrence? No. Long live cyber insurance!

[1] Joe Burton, Cyber Deterrence: A Comprehensive Approach? (Tallinn: The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, 2018), 4.

[2] Max Smeets and Stefan Soesanto, “Cyber Deterrence Is Dead. Long Live Cyber Deterrence!,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 18, 2020, https://www.cfr.org/blog/cyber-deterrence-dead-long-live-cyber-deterrence.

[3] Max Smeets, “A matter of time: On the transitory nature of cyberweapons,” Journal of Strategic Studies 41, no. 1-2 (February 2017): 6–32, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402390.2017.1288107.

[4] “Mutually Assured Destruction,” Nuclear Files, last accessed May 25, 2022, http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-weapons/history/cold-war/strategy/strategy-mutual-assured-destruction.htm.

[5] Tom Johansmeyer, “The Cyber Insurance Market Needs More Money,” Harvard Business Review, March 10, 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/03/the-cyber-insurance-market-needs-more-money.

[6] Jim Lewis and Chris Painter, “2021 in Review: All Things Cyber,” December 17, 2021, in Inside Cyber Diplomacy, podcast, https://www.csis.org/node/63447.

[7] Colin S. Gray, “Deterrence in the 21st Century,” Comparative Strategy 19, no. 3: 255, https://doi.org/10.1080/01495930008403211.

[8] Gray, “Deterrence in the 21st Century,” 256.

[9] Linn Foster Freedman, “Colonial Pipeline Up and Running After Five Days of Grappling with Ransomware Attack,” Data Privacy + Cybersecurity Insider, May 13, 2021, https://www.dataprivacyandsecurityinsider.com/2021/05/colonial-pipeline-up-and-running-after-five-days-of-grappling-with-ransomware-attack/.

[10] Tom Johansmeyer, “Damage to Ukraine’s renewable energy sector could surpass $1 billion,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, April 20, 2022, https://thebulletin.org/2022/04/damage-to-ukraines-renewable-energy-sector-could-surpass-1-billion/.

[11] Eric Grant, The Social and Economic Value of Insurance (Zurich: Geneva Association, 2012), 8, https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/research-topics-document-type/pdf_public/ga2012-the_social_and_economic_value_of_insurance.pdf.

[12] Marco Arena, “Does Insurance Market Activity Promote Economic Growth? A Cross-Country Study for Industrialized and Developing Countries” (Policy Research Working Paper No. 4098, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2006), 3, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9257.

[13] “The author is head of PCS. The views expressed herein are those of the author, based on research conducted by the author, and may not necessarily represent the views of others, unless otherwise noted. PCS, a Verisk business, generally provides data and analytics to the global re/insurance and ILS markets. PCS captures reported loss information on certain events, which encompasses, on average, approximately 70% of the market. Any reference to industry-wide is based on this research and the author’s view of trends in the industry, and does not necessarily represent the view(s) of others in the industry.”

[14] Munich Re, Munich Re Global Cyber Risk and Insurance Survey 2022 (Munich: Munich Re, 2022), 2, https://www.munichre.com/content/dam/munichre/contentlounge/website-pieces/documents/MunichRe-Topics-Cyber-Whitepaper-2022.pdf/_jcr_content/renditions/original./MunichRe-Topics-Cyber-Whitepaper-2022.pdf.

[15] Tom Johansmeyer, “Cybersecurity Insurance Has a Big Problem,” Harvard Business Review, January 11, 2021, https://hbr.org/2021/01/cybersecurity-insurance-has-a-big-problem.

[16] Christian Biener, Martin Eling, and Jan Hendrik Wirfs, “Insurability of Cyber Risks; An Empirical Analysis,” The Geneva Papers, (June 2014): 12, https://www.internationalinsurance.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/Insurability%20of%20Cyber%20Risk.pdf.

[17] Rachel Anne Carter, Darren Paine, and Julian Enoizi, Insuring Hostile Cyber Activity: In search of sustainable solutions (Zurich: Geneva Association, 2022), 23, https://www.genevaassociation.org/research-topics/cyber/insuring-hostile-cyber-activity-search-sustainable-solutions-research-report.

[18] “Insurance Linked Securities Investment Managers & Funds Directory,” Artemis, last accessed January 31, 2022, https://www.artemis.bm/ils-fund-managers/.

[19] Artemis, “Property cat still key area for ILS market growth, cyber close behind,” Artemis, November 23, 2018, https://www.artemis.bm/news/property-cat-still-key-area-for-ils-market-growth-cyber-close-behind/.

[20] Aaron C. Koch, “Casualty: The Next ILS Frontier?” Insurance Journal, August 6, 2018, https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2018/08/06/497146.htm.

[21] Steve Evans, “Cyber a growth compartment for the ILS industry: Millette, Hudson Structured,” Artemis, November 8, 2019, https://www.artemis.bm/news/cyber-a-growth-compartment-for-the-ils-industry-millette-hudson-structured/.

[22] Luke Gallin, “No fast way into cyber for ILS, say experts,” Artemis, November 27, 2019, https://www.artemis.bm/news/no-fast-way-into-cyber-for-ils-say-experts.

[23] Syed Salman Shah and Ben Dyson, “Cyber insurance-linked securities have arrived, but market still in infancy,” S&P Global Market Intelligence, October 12, 2018, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/cyber-insurance-linked-securities-have-arrived-but-market-still-in-infancy-46915334.

[24] Carter, Paine, and Enoizi, Insuring Hostile Cyber Activity, 23.

[25] One respondent has no direct commercial relationship with PCS. Not all respondents subscribe to PCS Global Cyber.

[26] The one respondent with “N/A” answers throughout the survey did not engage with PCS on this research but is known not to be active any longer.

[27] Questions were not necessarily asked in the order presented to facilitate the flow of conversation.