Maria Fantappie is a special advisor at the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue.

Theorists of consociation argue that it is the best kind of democracy a plural society can expect: a power-sharing formula that accommodates leaders representing different segments of the population, thus preventing one group from dominating the others. As Saddam Hussein fell in 2003, Iraqi opposition groups and US policymakers supporting the invasion of Iraq advocated such a system for the country’s future. Consociation promised democracy through proportional representation of Iraq’s main sects and ethnic groups—Kurds, Shia, and Sunnis—addressing opposition groups’ concerns that members of the Sunni community would once again come to dominate national politics. Like Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands, Iraq could have transitioned to democracy, the argument went, embracing a system where segments of its society, identified as the three main communal groups, would be fairly represented in the new state.

Iraqi politics have evolved otherwise. The newly empowered Iraqi leaders kept tight control of the political arena. They prevented representatives of other non-communal segments of Iraqi society from joining the political system and abused the principle of proportional representation across the bureaucracy to accumulate resources, weapons, and manpower. Western countries supporting the invasion backed this as a legitimate political process, supporting the ethno-sectarian quota as an instrument to ensure fair representation and political transition. Over the years, Iraq’s consociation has moved closer to that of Lebanon, in that a few leaders perpetuate rigid ethno-sectarian appointments and quotas they control, fail to deliver representation and good governance, invite foreign interference, and drive the country’s chronic political instability.

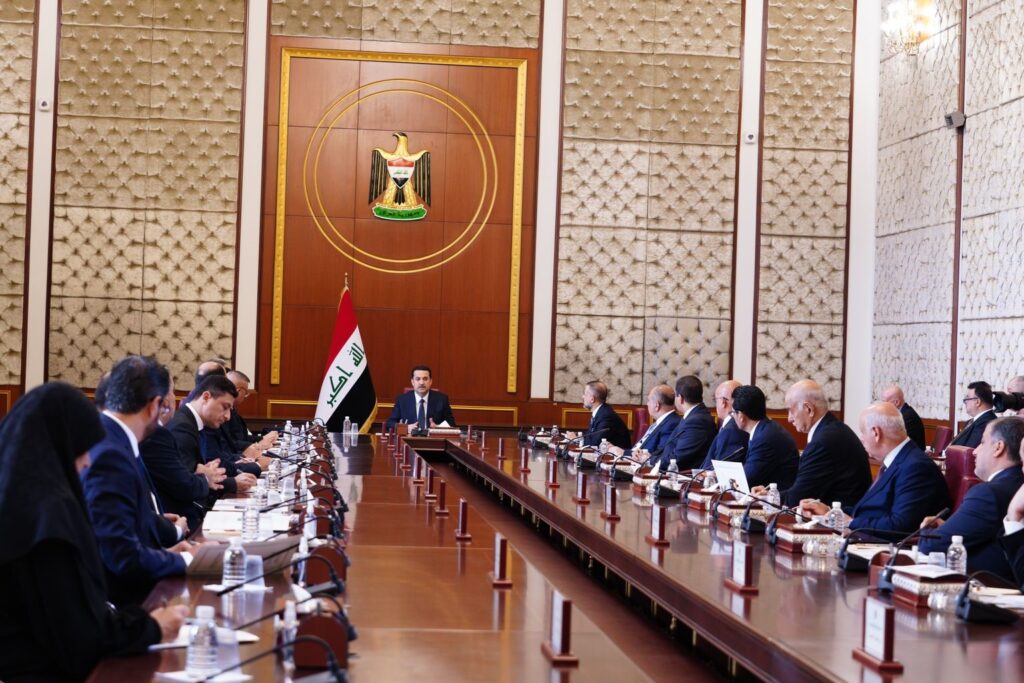

The tortuous path that led to Iraq’s most recent government formation in November 2022 demonstrates the failures of the country’s consociation. Following the October 2021 elections, it took a yearlong political stalemate, violence, and protests to form a new government. The standoff over Shiite politics—between Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr and rival Shiite political forces over the choice of prime minister and leadership—plunged the country into paralysis. Over the summer, tensions escalated when Sadrists withdrew from parliament. Sadr’s followers then stormed the Green Zone as rockets fell on parliament and rival Shiite forces voted in a new government headed by Mohamed Shia al-Sudani.

The formation of a new government in Iraq came as welcome news. But the government’s formation may only mark a fleeting moment of stability. This current government, as with previous ones, formed after its factions informally agreed to keep Iraq’s consociation as it is. The path forward is clear. Either consociation will prove flexible enough to move past its current form by integrating non-communal identities and new leaders, or it will lead Iraq into a downward spiral of instability.

Explaining Iraq’s Chronic Instability

In its current form, Iraq’s political system has eroded the space for competition and compromise, consolidating power in the hands of a diminishing number of individuals. The political parties that once dominated Kurdish, Shiite, and Sunni politics are in crisis. In 2005, Kurdish parties stood united in Baghdad bound by a strategic agreement, and Shiite parties cooperated with each other in a similar coalition. Now, Shiite parties’ leadership councils and Kurdish parties’ politburos are consumed with internecine fights and no longer function as platforms for competition, bargaining, and negotiation. Instead, a few individual leaders hold all the levers of power—political, economic, and military—and rely on co-optation and coercion to govern their constituencies. Increasingly, politicians exclude their competitors to become the lone representative of the Kurdish, Shia, and Sunni communities. Excluded politicians capitalise on the discontent this creates to mobilise masses and use coercion to prevail. Animosity between Kurdish leaders over the presidency and distrust among Shiite forces have cost Iraq twelve months of deadlock.

Ethno-sectarianism, a dominant feature of Iraq’s consociation, fails to represent the many non-communal identities that are prevalent throughout Iraqi society. Communal politics places emphasis on people’s communal ties above all else, reifying these groups as the only identities around which society can organise. While this helps traditional leaders and their heirs stay in power, it excludes leaders and movements representing the class, generational, or local identities that are increasingly salient among younger Iraqis. The 2019 civic uprising and the October 2021 elections created an opening for Iraq’s consociation to move past communalism. But that chance was spoiled. Following the elections, leaders did forge cross-sectarian alliances—including an alliance among the Kurdistan Democratic Party, Sunni leader Mohammed Al-Halbousi, and Moqtada al-Sadr—but only aimed at prevailing against their rivals within the existing system rather than building an alternative to communalism. A reformed Iraqi consociation could represent dominant identities emerging across society, including non-communal ones, and thus ensure more robust representation. Failure to do this can only fuel growing discontent and anti-establishment movements.

Iraq’s consociation has generated a public sector that is unfit to address demographic, economic and governance challenges facing the country. With a net population growth of a million people per year, an increasing proportion of working-age people, temperatures rising, and water supplies dwindling, Iraq urgently needs an agile and efficient bureaucracy. Iraq’s consociation is unable to deliver one. Proportional allocation of positions based on communal belonging and party affiliation neuters talents and practically sanctions inefficiency throughout the bureaucracy. Connections to powerful leaders, rather than work performance, define public servants’ prospects for employment, promotion, and corporate benefits. Technocrats, even if committed to reform, are unable to fire civil servants as long as they are backed by powerful parties, and they are forced to employ politically appointed functionaries to keep their allies happy and their rivals in check. Those few civil servants who are appointed in their post for their competence often face isolation and distrust in their work environments. Sustained by oil rent, the public sector has been expanding in size but diminishing its efficiency at a time when governance challenges have become increasingly urgent.

Most importantly, the unstable nature of Iraq’s consociation leaves the country vulnerable to political influence and military aggression from powerful foreign actors in the region. Iraq has become an arena where regional powers compete for strategic influence. Iran’s rivalries with Turkey, Israel, and the Gulf countries all play out on Iraqi soil. Turkey now has unprecedented leverage in continuing its military and drone strike operations in the Kurdish regions of northern Iraq, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made Ankara a more vital ally within NATO. With renewed self-confidence, Turkey and the Gulf countries view Iraq as Iran’s Achilles’ heel, a political battleground where engagement with Sunni, Shia, and Kurdish factions opposed to Iran can counter Tehran’s influence in Iraq and advance their own. In turn, Iran is likely to see Iraq’s new government as an arena to project deterrence and take offensive actions against its enemies Israel and the United States and to continue its recurrent bombing campaigns against Iraqi Kurdistan.

Moving Past Iraq’s Consociation

Iraq’s consociation has the potential to move past its current form because its most destabilizing aspects are informal arrangements, not constitutional law. While the Iraqi Constitution refers to a balanced representation, non-discrimination, and the inclusion of all components of the Iraqi people in Iraq’s armed forces, no article in the Constitution nor any law mandates the allocation of senior posts or state bureaucracy along ethno-sectarian lines. The fact that positions of president, prime minister, and speaker of parliament are always assigned to a Kurd, Shiite, and Sunni leader, respectively, is the result of an informal arrangement struck among members of the post-invasion elite and perpetuated throughout the public sector. Iraqi society has already shown resistance to these informal rules. Younger generations of Iraqis have resisted this system by mobilizing in mass protests. A small circle of civil servants across the administration, mostly younger, also rejects the practice of ethno-sectarian quotas for government jobs.

And yet, Iraq’s consociation continues to endure. The lack of foreseeable alternatives helped Iraq’s consociation survive this long despite its shortcomings. Post-Arab Spring politics across the region seemed to demonstrate the bleak binary choice between the centralized system of the Gulf monarchies and Egypt, on the one hand, and Syria, Yemen, and Libya, divided and ravaged by conflict, on the other. The prospect of either—the return to a highly centralized state or dissolution into a highly decentralized one—raises fears that Iraq may relapse into authoritarianism or may break off into separate entities.

Iraq’s consociation also endures because it offers predictable rules to Iraqis as well as regional and international actors. Most public servants—the majority of the country’s workforce—have perpetuated consociation by adhering to its rules and neutralizing resistance against it. For the past twenty years, millions of them have followed and reproduced the unwritten rules of this logic, which defines their career prospects, and beyond that, the structures of power across the entire society. International and regional powers have also legitimized and entrenched the existing rules of politics because it enables them to secure influence.

But anyone wishing for a stable Iraq would be wise not to take the formation of a government as the end of Iraq’s impasse but rather as a parenthesis between the most recent political crisis and the next one. They should be aware that the current rules of politics that formed the current and previous governments have now exhausted their potential and are leading Iraq into a cycle of similar crises.

Moving past Iraq’s consociation requires readiness to renounce the predictability that the status quo offers in the short term for the greater good of sustainable stability. The primary focus should be on reviving organs of collective decision-making within established political parties, such as politburos and leadership councils, and creating space for representatives of non-communal entities to take on parliamentary and executive roles. The international community should focus on supporting processes rather than political figures to help Iraq move past personality politics. The new Iraqi government must prioritize the reform of public sector employment, including the allocation of promotions and benefits, so that these are awarded on the basis of merit rather than political or communal affiliation. The Iraqi government should continue to pursue a diversified and balanced foreign policy to push back against interference from regional neighbours. The Baghdad Summit, which took place in Amman, Jordan in December 2022, was a positive step in this direction. All these steps will no doubt be met with backlash from those who benefit from the current system and fear losing power and influence under a revized system of consociation. But it is the only way forward. Only a reform of Iraq’s consociation would repair leadership-society relations, bolster the country’s capacity for effective governance, insulate the country from regional conflict, and help secure long-term stability in Iraq.

Works Cited

Arend Lijphart, Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1977), 1–24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1dszvhq.

John McGurry and Brendan O’Leary, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005: Liberal Consociation as Political Prescription,” International Journal of Constitutional Law 5, no. 4 (2007): 670-698, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brendan-Oleary-2/publication/31450711_Iraq’s_Constitution_of_2005_Liberal_Consociation_as_Political_Prescription/links/00b49529252a78772c000000/Iraqs-Constitution-of-2005-Liberal-Consociation-as-Political-Prescription.pdf.

Ali A. Allawi, The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2007), 62-77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1npg7d.

Toby Dodge, “The Muhasasa Ta’ifia and Its Others: Domination and Contestation of Iraq’s Political Field,” in Religion, Violence, and the State in Iraq, Project on Middle East Political Studies (Washington, DC: Elliott School of International Affairs, September 29, 2020), https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/POMEPS_Studies_35.1.pdf.

Taif Alkhudary et al., “A Summer of Danger for Iraq—With Little Hope for Change,” The Century Foundation, August 8, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/a-summer-of-danger-for-iraq-with-little-hope-for-change/.

“The Situation Concerning Iraq: Security Council Briefing,” United Nations, May 17, 2022, https://media.un.org/en/asset/k16/k163y537d9.

Martin Chulov, “Deadly Violence in Baghdad after Leading Cleric Moqtada al-Sadr Says He Is Quitting Politics,” The Guardian, August 30, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/29/followers-shia-cleric-storm-iraq-government-palace-muqtada-al-sadr.

“Rockets Hit Baghdad’s Green Zone as Iraq’s Parliamentarians Meet,” Al Jazeera, October 13, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/10/13/rockets-hit-baghdads-green-zone-as-parliament-prepared-to-meet.

“The Situation Concerning Iraq: Security Council Briefing,” United Nations, October 4, 2022, https://media.un.org/en/asset/k1e/k1e0vjaobw.

Bekir Aydogan and Mehmet Alaca, “A Family Affair: Rift in the Talabani Family Highlight the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s Political Weaknesses,” Fikra Forum, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 25, 2021, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/family-affair-rifts-talabani-family-highlight-kurdistan-region-iraqs-political.

Dana Taib Menmy, “Iraq Plunges into a Constitutional Crisis, yet to Elect a President,” The New Arab, April 6, 2022, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/news/iraq-enters-constitutional-crisis.

Julian Bechocha, “Leaked Maliki Recordings Threaten to Deepen Political Impasse in Iraq,” Rudaw, July 18, 2022, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/180720224.

Maria Fantappie, “Widespread Protests Point to Iraq’s Cycle of Social Crisis,” International Crisis Group, October 10, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iraq/widespread-protests-point-iraqs-cycle-social-crisis.

Farhad Alaadin, “Iraq’s Tripartite Alliance is Pressing, Framework is Threatening,” Rudaw, January 23, 2022, https://www.rudaw.net/english/opinion/230120221.

Alexander Hamilton, “Is Demography Destiny? The Economic Implications of Iraq’s Demography,”Middle East Centre, Conflict Research Programme (London, UK:London School of Economics, November 2020), 11, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/107411/1/MEC_is_demography_destiny_paper_41.pdf.

Lisa Binder et al., “Climate Risk Profile: Iraq,” Adelphi, July 26, 2022, https://www.adelphi.de/en/publication/climate-risk-profile-iraq.

Samya Kullab, “Salt, Drought Decimates Buffaloes in Iraq’s Southern Marshes,” AP News, November 23, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/europe-middle-east-droughts-animals-iraq-c2acc021f0e020811c2b5e55336cd845.

Maria Fantappie and Vali Nasr, “What America Should Do if Iran’s Nuclear Deal Talks Fail,” Foreign Affairs, July 1, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/israel/2022-07-01/what-america-should-do-if-iran-nuclear-deal-talks-fail.

“Turkey’s Military Operations in Iraq and Syria,” Reuters, November 21, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-military-operations-iraq-syria-2022-11-21/.

George Wright, “Iraq Accuses Turkey of Attack That Killed Nine in Kurdistan,” BBC, July 22, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-62246911.

Amina Ismail and John Davison, “Iran Attacks Iraq’s Erbil with Missiles in Warning to U.S., Allies,” Reuters, March 13, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/multiple-rockets-fall-erbil-northern-iraq-state-media-2022-03-12/.

“Iraq’s Constitution of 2005,” Constitute Project, April 27, 2022, https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Iraq_2005.pdf?lang=en.

Toby Dodge, “Iraq’s Informal Consociationalism and Its Problems,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 20, no. 2 (October 2020): 145-152, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sena.12330.

“Breaking Out of Fragility: A Country Economic Memorandum for Diversification and Growth in Iraq,” (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34416/9781464816376.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

“Baghdad II Summit in Jordan Aims for Progress on Iraq, Middle East Issues,” France 24, December 12, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20221220-jordan-hosts-baghdad-ii-summit-aiming-to-defuse-regional-tensions.