Morocco’s Multicultural Gateway to Community Development

Morocco’s policy for national multiculturalism and the diversity of its historic identity groups has emphasized the importance of intergroup dialogue and its role as a “bridge” to human development. In recent years, the Moroccan Ministry of Culture began collaborating with UNESCO to establish a framework for cultural preservation. The government has expressed the important role that culture plays in combating poverty through heritage preservation. They believe this will help empower individuals and increase their opportunities for social and economic mobility. Additionally, integrating a cultural dimension into education is considered a significant factor in encouraging development by promoting recognition and enhanced solidarity. Similarly, cultural preservation and awareness can specifically help women to enhance their livelihoods and economic prospects. In relation to sustainable urban development, preservation activities help to balance modernization, tradition, the environment, and public spaces.

Although pathways exist to foster intercultural partnerships to meet Moroccan communities’ needs, it continues to be a complex challenge. For example, interreligious partnerships may often find shared goals of preserving archives, sacred locations, and cultural knowledge. However, translating these goals into concrete initiatives that could lead to improved public health, enhanced livelihoods, and environmental protection requires more innovative and locally-led approaches.

Morocco represents a notable case where a unique Muslim-Jewish cooperation is leading sustainable fruit tree agriculture and human development, especially within clean drinking water, irrigation infrastructure, and financially independent women’s cooperatives, all achieved through building community-managed fruit tree nurseries. These nurseries, built on land lent by the Moroccan Jewish community, illustrate the ability of interfaith partnerships to address critical rural challenges. Morocco’s National Initiative for Human Development has provided a significant proportion of funding to construct four nurseries (two completed and two in the process) to provide trees to farming families who seek to transition from barley and corn to more income-generating organic fruit products. The integration of monitoring the trees planted by farming families for certified and commercialized carbon offset credits further enhances the community impact.

The pilot nursery, established in 2012 in the Tomsloht municipality, Al Haouz province, now produces 70,000 trees annually. This region was severely impacted by the September 2023 earthquake that occurred in the High Atlas Mountains, amplifying the significance of sustainable agriculture projects for post-disaster recovery. The second nursery, built in 2020 in the Ouarzazate province, has produced approximately 40,000 trees, with two additional nurseries in the process of being constructed in the Marrakech and Ouarzazate areas. All four nurseries are situated adjacent to Moroccan Jewish saints’ sacred burial sites, some dating back 1,000 years. With over 600 locations of religious significance in the country, interfaith and intersectoral partnerships effectively play a significant national role in assisting farming communities transition to fruit tree agriculture. They can together build a more resilient, economically enhancing, and healthier option than traditional reliance on growing barley and corn.

Morocco’s path of national solidarity for human development provides widespread benefits and exemplifies that there is a viable recourse from strife and division. The development process begins with local communities determining their development goals from an empowered disposition to help ensure that their decisions reflect their priority interests. From this empowerment workshop experience, leading to intercultural, public, and private partnerships based on dialogue and trust-building, communities assess and determine the most important projects they seek to implement.

Origins and Development of a Moroccan Cultural-Agricultural Program

In 1993, the author of this article volunteered with the Peace Corps living in a village of the High Atlas Mountains called Amsouzerte, where the journey from the village to the nearest city centers took almost 20 hours along unpaved roads and mountain passes. At the foot of a mountainside, fifty kilometers from Amsouzerte, there was an old, white mausoleum, uncharacteristic of the earth-brick homes typical of rural Moroccan landscapes.

Even at this time, it was immediately clear that eroding mountain areas offered large potential for terrace construction surrounding the mausoleum for the Muslim community to build tree nurseries and derive generational benefits. Tree nurseries are valuable for Moroccan farming communities because 70 percent of current agricultural land in the country generates just 10-15 percent of agricultural revenue. Fruit tree cultivation allows farming families to transition from less lucrative barley and corn crops to higher income-generating crops. Morocco has both organic and endemic varieties of almond, Argan, carob, cherry, date, fig, lemon, pomegranate, olive, and walnut trees among others, as well as dozens of species of wild medicinal plants.

Based on dialogue with farming families and communities, this local project was derived directly from their own determination and development perspective. The High Atlas Foundation (HAF)—a Moroccan national civil association founded in 2000 by former Peace Corps Volunteers who initially served in this mountain region–facilitated empowerment and participatory methods that assisted people in identifying their doubts and fears, project priorities, and actions forward to achieve their discovered goals of tree infrastructure and related water infrastructure.

In rural Morocco, where most household income is derived from agriculture, initiatives within this development sector, particularly surrounding water infrastructure, trees and herbs, cooperative-building, terracing, value-added processing, and marketing, are shared priorities across the countryside. The September 2023 earthquake exacerbated the need for these long-held priorities of farming families and brought them to the forefront for investment.

Small landholders often cannot commit the necessary land resources over the two years required for fruit tree seeds to mature, as they must harvest every season from all available land to maintain their livelihoods. The question that arose at the onset of the project and that remains prevalent for rural communities today is where land for nurseries will come from, if farmers cannot afford to convert their existing farmland.

The mausoleum near Amsouzerte is a sacred tomb of a Hebrew saint (tzaddik, or ‘righteous one’) named David-Ou-Moshe, one of over 600 tzaddikim (Muslim, Jewish, and Christian) buried throughout Morocco. The land immediately around these burials had potential for future tree nurseries that could generate tens of millions of saplings annually.

On behalf of the farming families, HAF approached the Moroccan Jewish community to request land leases for building tree nurseries on this land. While they agreed, sufficient funding was still needed for the project to commence. Although the original location remained undone as years passed, a successful pilot nursery launched in 2012 at Akrich in the Al Haouz province near Marrakech at the burial site of another tzaddik named Raphael Hacohen that has since collaborated with and provided benefits for 175 different farming families annually.

Community nurseries jumpstart a new development path toward economic and environmental sustainability. The Akrich tree nursery, for example, led to empowerment workshops and the establishment of the nearby Achbarou women’s carpet-making cooperative, the construction of a paved road between the nursery/cemetery and the cooperative that allows visitors to easily visit both sites, and a clean drinking water system in Achbarou village. It is necessary that agencies partner with communities like Achbarou as land contributors to catalyze human development projects that extend benefits beyond the agricultural sector.

Methods of Scaling Cultural Initiatives and Sustainable Development

Moroccan development policies and the public have recognized the environmental richness and symbol of social solidarity that the country bears. Environmentally, the natural diversity composed of distinct biozones (which exist in the Middle East and North Africa region at large) has created widespread opportunities for food production generated from endemic species.

Socially, the Moroccan national identity includes people of different ethnicities, languages, dialects, and faiths. In general, Morocco represents one case in which people of varying identities live unified under a single sovereignty in relative harmony. Morocco, as apparent in its culture, policies, and constitution, aims to embrace the different aspects that make up its identity. Even in the current regional context of conflict and war, Morocco maintains a commitment through policy and programs to the diversity of faiths for its communities as a pathway towards improving people’s lives. This approach is seen as the most practical way to achieve development and inspire broader peace and acceptance across the world.

However, in order to attain enduring success in this way, interfaith actions require their design to come from the community beneficiaries and directly address their self-described needs. Development implemented through local participatory methods generates the critical trust and goodwill that strengthen social unity, due to its responsiveness to the will of the people. Necessarily, Morocco’s commitment to community-identified and managed initiatives for growth is also embedded in Moroccan policy, strategic plans of ministries, charters, and the Constitution.

After coordination with the Ouarzazate governor and with the Regional Directors of relevant public agencies, construction of the new nursery began in 2019. In the past four planting seasons, over 46,000 fruit saplings were produced at this nursery that were then planted in the private agricultural lands of 195 small landholder families, marking significant progress for the development trajectories of these communities. Lands for future nurseries are increasingly being set aside by the Moroccan Jewish community to contribute to this interfaith organic fruit tree initiative, titled House of Life by the governor of the Al Haouz Province Younès Al Bathaoui, denoting the traditional title for a Jewish cemetery.

Monitoring the Trees for Verified and Commercialized Carbon Offset Units

Monitoring tree nurseries for evaluating carbon offset credits has also become an integral part of the larger tree-planting initiative. New carbon offset programs and verification standards integrate multiple existing methodologies to launch community initiatives through participatory development and empowerment workshops, particularly with women. This strategy utilizes local, organic, and endemic seed varieties; incorporates renewable energy in the form of solar water pump systems at nurseries; reinvests offset revenue in new community projects within the regions that generated the credits, and concentrates tree planting with small landholder farming families, all while facilitating interfaith collaboration to alleviate rural poverty.

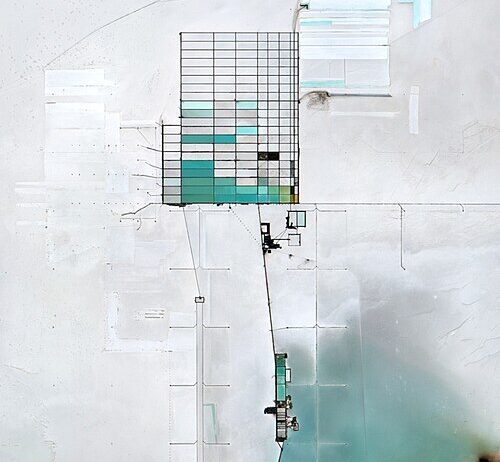

Observing tree growth using GPS, maintaining registries and GIS maps of planted trees, and monitoring voluntary and credited carbon offsets with certifiable systems are critical components of the nursery programs. Monitoring systems include important data such as the farmer’s name, association, or cooperative, the village and region, the tree species and number of trees, photos of the location, planting systems used, and other factors to ensure maximal efficient use of all land.

Using the current carbon credit monitoring system (that of PlanVivo based in Scotland), 80 percent of the value of the carbon offset credit (now valued at 40 euros) returns to the farmers and their development projects. Of the remaining 20 percent of the value of the credit, 10 percent goes to the certifier who helps verify and commercialize the credit, and 10 percent goes to HAF for the costs of ongoing monitoring, organizing community meetings for project identification, securing authorizations with relevant public agencies, overall implementation, and financial and programmatic compliance (including audits).

As stated in Morocco’s General Report of the New Development Model, significantly more investment is necessary in order to achieve the levels of economic growth and poverty alleviation needed, with an emphasis on agriculture, human capital, and digitalization. These components are all integral in the House of Life and carbon credit offset programs. Furthermore, the focus on family farmers helps to ensure that the benefits are directed at the communities and villages that need them most.

The sector that presents the greatest likelihood of return, and which addresses the core of the poverty affliction in the country, is agriculture. The agricultural practices that prevent people from taking full advantage of the sector’s opportunities are the same practices that, if positively transformed, will uplift millions from poverty and secure environmental sustainability and water availability for decades to come. Therefore, targeting investment in the agricultural sector and ensuring that it is delivered to the communities is what will accelerate and multiply the level of financial returns for overall human development.

Although significant barriers exist to securing new financing that reaches farming communities, they can be addressed to create new projects by the people. For example, compliant financial and programmatic management and reporting systems of local civil and cooperative groups are essential but too few in number. In this regard, capacity-building is vital, and having an enhanced self-reliant form of revenue generation is key, especially one derived from an ongoing production activity that already exists like fruit tree agriculture.

Added income from the verification and sale of carbon offset credits enabled by tree planting activities can capitalize on communities’ existing strength and further increase household income and reinvestment in local development. When interfaith partnerships—in this case, through the free provision of land for community nurseries—are a principal part of program implementation and expansion, they will become more prevalent and strengthen social solidarity as income and reinvestment from agricultural yields and carbon credits are generated.

Conclusions: Communities’ Discovery and Empowerment First

Morocco’s policies encourage intercultural dialogue and communication for human development. Different faith communities in Morocco are brought together to share their historical narratives, which can lead to improved livelihoods and health through a participatory development approach by leveraging underutilized capacities. However, these experiences that are necessary to empower and promote sustainable growth are too infrequent to impact social transformation. House of Life cements the continuity of interfaith collaboration, key for achieving scale and social change, by providing needed trees and support for new community projects.

While multicultural memory and consciousness in the country create opportunities, combining these factors has yet to reach the level of self-reliant development and a circular economy that the people urgently need. Through the USAID Dakira program (or “Memory” in English), civil society organizations and public administrations seek to redress the lack of such participatory community dialogues in which people discuss the past and the future together and create a shared vision forward.

Third-party facilitation of dialogue and communication at the community level is vital, especially in the initial phases, as cultural narratives and development opportunities are shared by the group participants, trust and cross-relationships are built, and future growth plans are created. In this way, Moroccan culture has become a (re)discovery gateway for human development, recalling the nation’s journey of diversity, unity, and solidarity, even through difficulty. Community storytelling helps people understand their connectivity and reliance on each other to achieve their individual and collective dreams.

The most significant challenge for participatory planning is the need for more training in community dialogue facilitation to empower all voices and express all priorities. While manifold methods and activities can be used to explore personal and collective identity and create plans for the future, most people have never experienced these approaches and are, therefore, unable to initiate and steward the process.

In recent years, the global community has seen that much of the world does not reflect the same model of faith and cultural solidarity. As can be seen, in the violent incidents at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2019, an African Methodist Episcopal church in South Carolina in 2015, and the Or L’Simcha Congregation synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018. In each of these cases, the killers were initially warmly greeted by their communities with “Salaam,” “Welcome,” and “Shalom” before they committed murder. Tree nursery projects, like the Akrich nursery, have the potential to juxtapose these atrocities against the more hopeful reality of interfaith solidarity as is experienced in Morocco.

Interfaith dialogue, as an opportunity to voice our histories, can deepen understanding and provide reconciliation between historically antagonistic groups. When this process is maintained and integrated with supporting projects and defined and managed by the people, it can become a basis for achieving sustainable and prosperous societies. In Morocco, interfaith connections are convivial when they occur but demand total energy and commitment to organize. This Moroccan approach to success across religious differences could inspire other nations of Africa, the Islamic World, and the Middle East to follow the same path.

Reference

Al Kaderi, M. (2014). Compendium Country Profile Cultural Policy in Morocco. Cultural Policy in the Arab Region. https://www.culturalpolicies.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/morocco_full_profile_2014.pdf

Anouar, S. (2022, November). Morocco Vows to Share Heritage Preservation Know-How Within Africa. Morocco World News. https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2022/11/352691/morocco-vows-to-share-heritage-preservation-know-how-within-africa

BBC. (2020, 24 August). Christchurch shooting: Gunman Tarrant wanted to kill ‘as many as possible’. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-53861456

Ben-Meir, Y. (2006). Create an Historic Moroccan-American Partnership. International Journal on World Peace. 23(2), 71-77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20752735

Ben-Meir, Y. (2019). Empowering Rural Participation and Partnerships in Morocco’s Sustainable Development. Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective. 14(2), 191-214. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol14/iss2/13

CBS. (2023, 27 October). Commemorating the 11 lives taken five years ago in Pittsburgh synagogue shooting. https://www.cbsnews.com/pittsburgh/news/commemorating-the-11-lives-taken-five-years-ago-in-pittsburgh-synagogue-shooting/

Circular Ecology. (n.d.) Wider Benefits of Carbon Offsetting. https://circularecology.com/wider-benefits-of-carbon-offsetting.html

El Khadiri, S. (2022, March). Participatory Approach with Women of Achbarou Cooperative. High Atlas Foundation. https://highatlasfoundation.org/en/insights/participatory-approach-with-women-of-achbarou-cooperative/

Empowerment Initiative. (2016). IMAGINE. Clinton Global Initiative 2014 Commitment to Action. https://imagineprogram.net/

Freeman, T. (n.d.). What is a Tzaddik? Being human all the way. Chabad.org. https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/2367724/jewish/Tzaddik.htm

High Atlas Foundation. (n.d.). Balance Your Carbon Footprint: Plant fruit trees with the High Atlas Foundation. High Atlas Foundation. https://assets.highatlasfoundation.org/uploads/PRINT-EN-HAF-Carbon-Offsets-Brochure-2023-A5-Document.pdf

High Atlas Foundation. (n.d.). Carbon Credits. High Atlas Foundation. https://highatlasfoundation.org/en/our-work/carbon-credits

High Atlas Foundation. (2023, January).High Atlas Foundation Plants Thousands of Trees with Moroccan Communities for Annual Tree Planting. BusinessGhana. https://www.businessghana.com/site/news/general/278143/High-Atlas-Foundation-Plants-Thousands-of-Trees-with-Moroccan-Communities-for-Annual-Tree-Planting

High Atlas Foundation. (n.d.). House of Life: Intercultural Organic Fruit Tree Nursery Initiative. High Atlas Foundation. https://assets.highatlasfoundation.org/uploads/EN-House-of-Life-Brochure-2023.pdf 43

Kuwait News Agency. (2008, August). Moroccan King Inaugurates 30th Asilah Cultural Festival. https://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticlePrintPage.aspx?id=1929008&language=en#

New York Times. (2015, 17 June). Nine Killed in Shooting at Black Church in Charleston. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/18/us/church-attacked-in-charleston-south-carolina.html

Plan Vivo. (n.d.). Acorn. Plan Vivo: For nature, climate, and communities. https://www.planvivo.org/acorn

Royaume du Maroc. (2021, April). The New Development Model: Releasing energies and regaining trust to accelerate the march of progress and prosperity for all. Royaume du Maroc General Report. https://www.csmd.ma/documents/CSMD_Report_EN.pdf

United Nations Alliance of Civilizations. (2022). Fez Declaration on the Ninth Global Forum of the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations: Towards an Alliance of Peace: Living Together as One Humanity. 9th Global Forum United Nations Alliance of Civilizations. https://diplomatie.ma/sites/default/files/inline-files/Fez%20Declaration-%20Adopted%20%2822Nov-%20End%20of%20Ministerial%20Meeting%29.pdf

United Nations Development Programme. (2023, April). What is circular economy and why does it matter? UNDP Climate Promise. https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/what-is-circular-economy-and-how-it-helps-fight-climate-change

U.S. Agency for International Development. (n.d.). Dakira. USAID From the American People. https://www.usaid.gov/morocco/fact-sheets/dakira

Walaw. (2024, November). Morocco Strengthens Legal Framework for Cultural Heritage Protection. https://sport.walaw.press/en/articles/morocco_strengthens_legal_framework_for_cultural_heritage_protection/GMXMRFSQLSWQ