As India becomes more urbanized, there will be significantly higher demand for public services and welfare support in urban areas. There is a need to extend income and consumption support schemes, similar to the flagship rural employment scheme (MNREGA), into urban areas, strengthening social safety nets and advancing human development gains. Concerns remain around its macroeconomic implications, the feasibility of such a scheme, and what the policy design of such a mechanism would look like.

India’s evolving rural-urban demography

In 2018, India had the second largest urban population in the world, at 461 million, or 34% of the country’s population.[1] In addition, India is projected to add 416 million people to its urban population between 2018 and 2050, nearly doubling its urban resident count. As a result, India will likely have a large and growing population of urban residents, largely migrant workers, with little in terms of a social safety net.

While GDP growth has accelerated since the start of economic reforms in 1991, and poverty levels have fallen, deprivation remains a major challenge. Using a consumption-based approach, the NITI Aayog—The Government of India’s Policy Think Tank—estimates that the poverty headcount fell from 29.2% of the population in 2013-14 to 11.3% by 2022-23.[2] However, while poverty has undeniably decreased in India, a substantial share of the country’s population remains at or near subsistence levels, necessitating strong government support.

In urban areas, conventional money-based poverty does not capture the extent of deprivation. Our argument is not about the extent of deprivation, but the fact that it exists, and more importantly, that the mechanisms for supporting marginalized groups in urban areas need to be buttressed, especially as India’s urbanization process continues to gather steam. As Rajan et al[3] show, temporary migrants (i.e. migration for purposes of work) are highest among the most vulnerable caste groups moving from poorer and more rural states (for instance, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh) to richer urban areas. Therefore, welfare policy intervention becomes even more significant.

Theories of Migration and Urban Poverty

Migration has classically been attributed to pull factors (i.e. considerations that individuals are attracted to, rather than escape from).[4] Li’s seminal econometric works in the 1960s codified pull and push factors; pull factors included higher incomes, safety, and most importantly access to formal and informal labor markets. Lewis (1955)[5] inculcated his theory of structural transformation with the movement of migrant labor as a natural requirement of moving from traditional to modern sectors, creating an argument explaining the movement of workers from rural to urban areas. The Lewis model, however, does not empower migrants’ agency in the decision to move, imposing a macroeconomic process on microeconomic decision-makers; it marginalizes voluntary decisions to migrate. It also assumes full employment, which fails to explain the concentration of masses in urban ‘modern’ sectors despite only marginal increases in industrial employment.[6]

The Neoclassical theory of migration, which focuses on the individual decision, states that the motivation to migrate is based on wage differentials as the starting point, rather than a Lewis-style structural transformation. However this model lacks in its simplification of labor markets; the labor market cannot perfectly balance supply and demand.[7] Periods of disequilibrium should be considered the norm and provisions should be made for these periods, rather than assuming labor market clearing.

Todaro’s (1969)[8] theory of rural to urban migration builds on wages as a pull factor. Considering that urban areas in less developed countries these days do not provide full employment, the model states that migrants have a much more complex optimization function in the decision to migrate. Migration is not determined by present higher wages but by differences in expected earnings. This means that migration without guaranteed employment is not only possible but a rational response to the wage differences between rural and urban areas. Expected living standards can draw rural populations into urban areas in addition to higher expected earnings. These may also skew intertemporal decision-making, where the expectation of future earnings can distort incentives to consume, invest, and continue to wager in finding urban employment rather than return to their place of origin.

There are also a multiplicity of theories that support non-economic factors to move, including ecological distress, declining agricultural opportunities, debt cycles, demographic transitions, etc.[9] In India, historically, the urban poor were seen as a result of distress migration and is largely assumed to be temporary as casual laborers sought an extra source of income during lean agricultural seasons. However, recent decades have shown a different migration pattern; while rural workers still migrate temporarily, they now tend to in urban areas for extended periods, often for the length of their working age. This likely owes to several factors, including stagnation in rural areas and faster growth in urban areas, including the emergence of the gig economy. While urban employment is often not reflective of the pace of wealth creation in urban areas, this is not inhibiting rural-urban migration.

Urban poverty is also largely seen as a negative side effect of labor migration.[10] While this is very much a reality in certain segments of the Indian population today, labor mobility generally entails significant portions of the rural poor’s livelihoods. Labor mobility is not just viewed as an incapacitated decision but a characteristic of the group itself. It is also the government’s role to provide anti-poverty measures, rather than blame the problem on migration, the latter of which is an established and legitimate economic phenomenon, the former, which should not be. Moreover, what Todaro describes as the ‘urbanization of poverty’ is not just an unemployment problem; social welfare (or lack thereof) in urban areas for migrant workers, substandard living infrastructure, and basic necessities such as health and education all contribute to urban poverty, exacerbating multidimensional inequality even if wages are profitable for workers.

Urban Welfare Policy in India

Strides have been made in welfare policies targeting urban areas in India. These schemes have targeted a range of pain points in urban development, ranging from infrastructure to skill development, credit subsidies, and female economic emancipation. The following (Box 1 and Box 2) are not exhaustive but aim to capture some of the types of schemes that are available. In these, we aim to capture the design of both job creation, as well as social infrastructure schemes launched by the government. The two we discuss are the National Urban Livelihoods Mission, and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Prime Minister Housing Scheme).

Box 1: The National Urban Livelihoods Mission

The Indian government initiated NULM in 2013, aiming to “reduce poverty and vulnerability of the urban poor households by enabling them to access gainful self-employment and skilled wage employment opportunities, resulting in an appreciable improvement in their livelihoods on a sustainable basis, through building strong grassroots level institutions of the poor.” It covers 4041 statutory towns and cities (all urban settlements with a population of more than 100,000), essentially covering the urban population of the country.

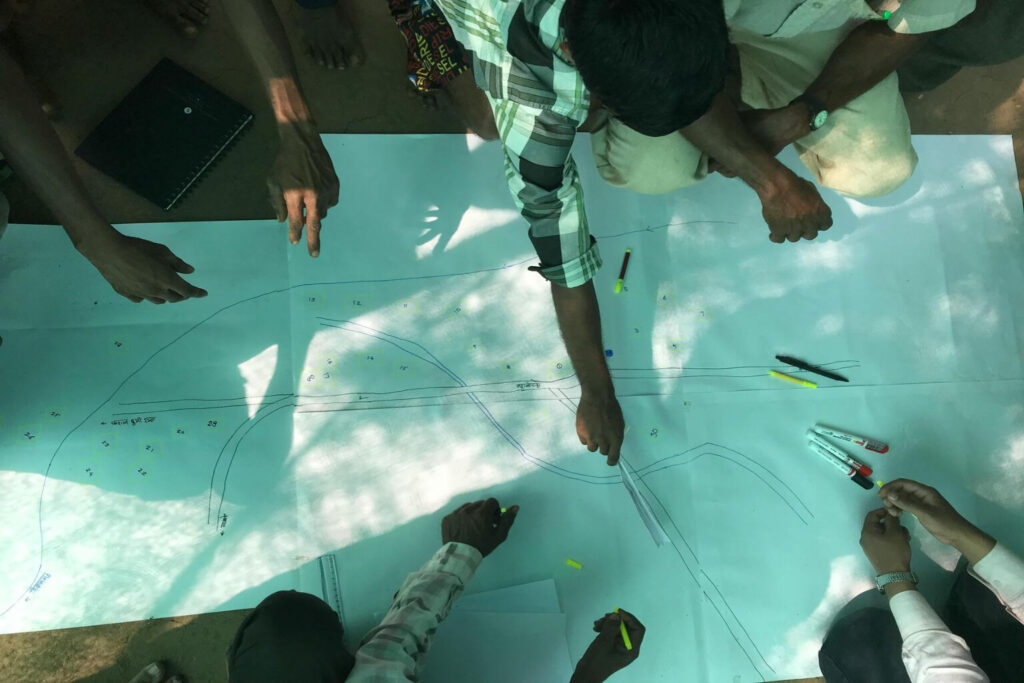

The NULM postulates that the poor are entrepreneurial; the poor will be provided the necessary tools to create assets that provide upward mobility. This is predicated on the improved bargaining power of the poor, which comes from building their own institutions that will lead to sustainable development through ownership and involvement of productive assets.

The hallmark of this scheme is its engagement through self-help groups (SHGs). . Several of the sub-schemes require SHG recommendations to enroll into, so it is an effective way to organize groups and enhance their bargaining power in various socio-economic aspects. NULM is primarily sponsored by the Central Government with a 60/40 split with in most states. However, the scheme also gives states enough autonomy to decide the sort of services, skills training, and shelter that may be specific to the local requirements or skill sets of the urban poor. This takes removes away fiscal strain from the states while giving them some autonomy and access to a nationally standardized quality of services.

Box 2: Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana

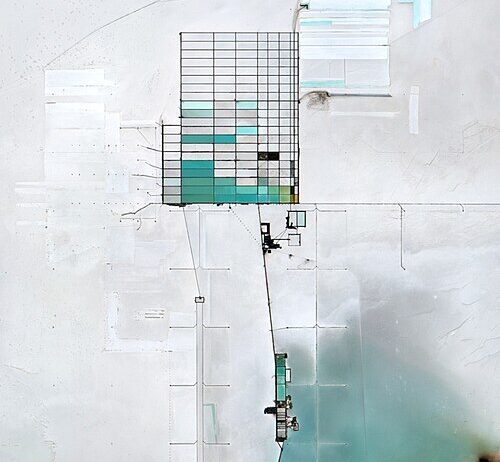

Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana is an urban housing scheme that has been implemented since 2015 to provide all weather-resistant brick cement houses to all eligible beneficiaries in the urban areas of the country. The scheme covers urban areas under the 2011 Census.

Key Learnings The Central Government has largely focused on capacity-building to build resilience to the vagaries of urban life. The government has enacted subsidized credit or consultative housing schemes rather than unconditional cash transfers, employment, or housing. To prevent moral hazard problems that arise from unconditional transfers, these schemes require some level of insurance (SHG recommendations) and effort into the process. These schemes also help to increasingly financialize poorer sections of society, which can have numerous benefits for individuals (i.e. improving savings behavior, social security access) and the state (i.e. channeling savings into investments, improved taxation, etc.). However, these schemes do not have the sort of uptake that is representative of the country’s urban population.

Moreover, state governments offered employment schemes during the COVID-19 pandemic, arguably because individuals needed access to discretionary spending over and above housing. Training- and upskilling-related schemes are also predicated on the notion that the issue at hand is a lack of skilled workers in urban areas, which may not be the case. While training and upskilling undoubtedly improve chances of upward mobility, they do not guarantee work in highly competitive urban environments.

A National Urban Unemployment Scheme

Developing an urban employment mechanism on the lines of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGA) would serve as a medium to channel underemployed workers and as a force multiplier to investment efforts improving urban infrastructure.

An urban employment guarantee scheme can offer unskilled employment up to a maximum number of days for a set daily wage. This amount should be high enough to support the increased costs of living in urban areas. But it should not be so high that it draws in additional rural workers who may not be absorbed after their time in the scheme ends (i.e. by offering higher compensation than MGNREGA plus the cost of relocation[11]). Additionally, this scheme should not be a permanent absorber of urban unemployment since such schemes tend to be sticky especially if wages are above minimum wage. With wage rigidities, the elasticity of labor supply will be greater than one and if the demand for labor increases, wage setting needs to consider this carefully. Benchmarking exercises of other schemes across India and close consultation with MGNREGA would support these efforts.

There is merit in separating employment on a spectrum of unskilled to partially skilled work under different categories. This would match workers engaging in familiar work. Separation of work in this manner can allow workers to specialize in developing on-the-job skills instead of taking time away from the labor market to improve their prospects for jobs outside the scheme. Separation of work may also encourage workers to upskill and exit from the scheme to find other better-paying opportunities at higher wages. This may also prevent arbitrage of workers moving from one unskilled program to another (i.e. MGNREGA). A wage level that ensures that the scheme is not a permanent absorbent of urban workers, along with upskilling, could provide a durable supply of workers to the private sector, especially given the ongoing focus on infrastructure, and create significant positive cyclical effects on the economy.

There are significant challenges in running a scheme like this, including the level to which local governments need to lead implementation efforts. Urban local governments, such as municipal bodies, have their own menagerie of problems, most notably their lack of fiscal and governmental independence from state governments. The scheme could be run through the same mechanism as NULM, namely SHGs. Job cards can be Aadhaar-linked[12] rather than residence-linked and a centralized database to prevent leakage from MGNREGA to this scheme can be created. Alternatively, this may be an opportune moment to reform urban local governments, giving them increased autonomy and piloting that autonomy through this scheme. It is better to use preexisting bodies rather than developing new institutions such that positive network effects can spread the scheme. Such an urban scheme must be initiated in the larger cities, as they hold the largest share of migrant workers from rural areas who are vulnerable to the sort of income loss that was experienced during the pandemic. On a more detailed level, any scheme must be implemented based on city-level inequality/unemployment data.

Conclusion and Future Avenues of Research

Poverty schemes have leaned towards the rural side when they were the engines of development. This is no longer the case, and neither the Lewis style nor Neoclassical theories of wage differentials are bringing enough people out of poverty in urban areas.

Migration is not necessarily a function of distress, but also of agency. Urban poverty is thus not a seasonal problem that swells during lean agricultural seasons, but a persistent problem that is not being supported by governments. There is significant evidence to suggest that the movement of rural workers to urban areas is of a longer-term temporary nature (i.e. it is not related to agriculture harvesting patterns). It is often linked to a general lack of opportunities in rural areas. India is now firmly on the way to becoming more urbanized; to the point that urban areas cannot be ignored in either policy or political considerations.

While employment is not the only reason for migration (other aspirations include improved amenities, health, education, housing, lifestyle, etc.), it is a significant reason. Therefore, employment schemes can enhance the entrepreneurialism, savings, and credit development of persons at or near subsistence levels in income terms, by giving them agency in their decisions. Non-employment-related urban schemes have had mixed success as they were not necessarily representative of the scale of urban challenges and have often focused on issues such as housing for instance, instead of creating a labor market safety net that can be counted upon to smoothen fluctuations caused by economic vagaries. What our proposal entails is a mechanism to ensure that shocks such as COVID-19 do not lead to significant consumption loss.

There are several macroeconomic considerations for a scheme like this such as center-state splits in funding, inflation, fiscal burden, labor market distortions, productivity, and macroeconomic issues like governance, corruption, and public support. Further research into these areas will subsequently enrich the growing calls for an urban unemployment scheme in the country today.

Notes

[1] United Nations. “World Urbanization Prospects 2018” UN DESA. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Feb/un_2018_wup_highlights.pdf

[2] NITI Aayog (2023) “ India National Multidimensional Poverty Index: a progress report” https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-08/India-National-Multidimentional-Poverty-Index-2023.pdf

[3] Rajan, S; Keshri, K; Deshingkar, P (2023) “Understanding Temporary Labour Migration Through the Lens of Caste: India Case Study” Migration in South Asia, pp 97-107, IMISCOE Research Series.

[4] Ravenstein, E.G. (1885). “The Laws of Migration.” Journal of the Statistical Society of London.

[5] Lewis, W. A. (1955). ‘The theory of economic growth’. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

[6] Papaelias, T. (2013). “A theory on the Urban Rural Migration”. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration. Volume I, Issue 4

[7] Gurieva, K. and Dzhioev, A. (2015). “Economic Theories of Labour Migration”. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. Volume 6. No. 6.

[8] Todaro, M. P. (1969, March). ‘A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries’ American Economic Review, 59

[9] Rajan, S; Keshri, K; Deshingkar, P (2023) “Understanding Temporary Labour Migration Through the Lens of Caste: India Case Study”. Migration in South Asia, pp 97-107, IMISCOE Research Series.

[10] Arjan de Haan, (1999), Livelihoods and poverty: The role of migration – a critical review of the migration literature, Journal of Development Studies, 36.

[11] Basole, A., Shrivastava, A., Narayanana, R. Swamy, Rakshita. (2020). “Is it time for an ‘urban NREGA’?” International Development Review. Available at: https://idronline.org/is-it-time-for-an-urban-nrega-employment/

[12] Aadhar is India’s centralized 12-digit national ID number.