Kyilah Terry is a Princeton in Africa Fellow in Nairobi, Kenya. She previously worked as a Policy Fellow with the Office of the Vice President. Kyilah holds a B.A. from UCLA, a M.A. from Georgetown University, and is matriculating into a Ph.D. program in Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania.

Aishwarya Rai is a Princeton in Africa Fellow in Nairobi, Kenya. She holds a M.A. in International and Development Economics from Yale University and a B.S. from Seton Hall University. She previously worked with the UN Office of the High Representative for Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries, and Small Island Developing States.

Asa Cooper is a Princeton in Africa Fellow in Nairobi, Kenya. He holds a M.A. in Law and Diplomacy from Tufts University, an M.A. in International Affairs from the American University of Paris, and a B.A. from the University of Georgia. He also works for Conflict Dynamics International.

By the end of 2022, as a result of conflict, drought, food insecurity, and localized violence, East Africa hosted an unprecedented 17 million forcibly displaced persons. Of this population, half are women and girls. They experience displacement differently from men and boys, as they are exposed to distinct risks throughout all phases of their displacement. Moreover, they face greater challenges in securing a livelihood, accessing education and healthcare, and ensuring their own protection. As a result, their needs differ, as do their resources, capacities, and coping strategies.

A large portion of the 8.5 million women and girls displaced in East Africa are likely to migrate to Kenya’s northeastern Garissa County, where nearly 280,000 forcibly displaced persons live in the Dadaab refugee complex or Somalia’s Benadir camps which host 422,000 people. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in these camps have implemented programs that aim to make gender equality a core principle of their humanitarian response. However, a safe situation inside any refugee camp is far from assured.

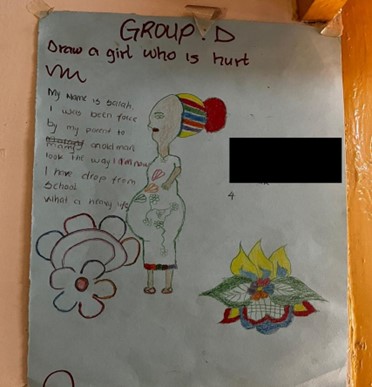

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), trafficking, early and forced marriage, female genital mutilation, and intimate partner violence have increased amid drought, famine, COVID-19, high unemployment rates, and conflict. Reports of physical violence nearly doubled in Dadaab between 2019 and 2021, and in parts of Somalia where girls are victimized at increasingly younger ages. This type of violence is not only committed by other refugees and host community members, but by aid workers, as well. While humanitarian actors have committed to women’s empowerment and safety, these commitments are difficult to realize. With another camp opening in Dadaab, however, humanitarians have an opportunity to implement more meaningful interventions that address gender-specific protection gaps in protracted displacement contexts.

This article explores how displacement exacerbates pre-existing vulnerabilities for women and children in East African refugee camps, and how their protection and security can be strengthened through a series of client-informed security, migrant protection, and development policies.

An Architecture of Insecurity

Refugee camps are temporary facilities built to provide immediate protection and basic assistance, in the form of food, water, shelter, and medical treatment, to people who were forced to flee their homes. As this definition makes clear, refugee camps are not permanent solutions. And as the crises that initially forced people to leave their homes become protracted and evolve, camps are unable to fully accommodate those facing long-term displacement. Yet, for some protracted refugee crises, the average length of stay in a camp can last decades. The architecture of these camps, which includes the design as well as facilities and staff, is unsustainable and exposes women and girls to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

In most camps, latrines are separated by gender. Though gender-separated latrines were intended to mitigate potential violence against women, it can have the opposite effect. With fathers and brothers unable to accompany their female relatives to toilets, which sometimes lack a locking mechanism, incidents of sexual violence at latrines occur far too often. Moreover, poor lighting often dissuades women from using the latrines at night as many rightly believe that darkness provides a cover for crime. In Kenyan refugee camps, 40 percent of SGBV cases happen at night, and a significant number of survivors are children. As a result, women sometimes refuse food and water for multiple days to avoid using the latrines, leading to health risks such as malnutrition, as well as unsafe coping mechanisms like defecating in the open.

Decentralized or unevenly distributed facilities also increase the risk of SGBV. In Dadaab, hospitals, clinics, schools, boreholes, and police precincts are on different ends of the complex. This life-threatening inconvenience means women and girls must walk farther, increasing the likelihood of assault. While humanitarian organizations work to address this through initiatives such as safety training for local motorcycle riders, who transport residents across the camp, women are still at risk from the drivers themselves and riders can be unavailable during emergencies. Decentralization also contributes to a lack of privacy for women and girls. Reproductive health clinics are isolated but still visible. Safety concerns, as well as shame and stigma can arise from being seen entering these facilities, discouraging women from accessing health services.

Staff and personnel are essential, but overlooked, elements in the architecture of camps, as a scarcity or poor quality of staff can prove fatal for women and girls. A lack of security staff, especially at night, increases risks for women and can lead to victimization. And a dearth of administrative, counseling, and legal staff, especially of women aid workers who speak the local language, can contribute to long wait times for critical support services. However, even when staff is available, some residents feel disrespected and not listened to, dissuading them from seeking help. Humanitarian organizations aim to ensure forcibly displaced persons can live in dignity through their services, but there is often a disconnect between this intention and how these organizations provide aid to the displaced.

According to the UN Office of the High Commission for Humanitarian Affairs, all humanitarian personnel ought to assume gender-based violence is occurring and threatening affected populations, but the report does not mention assault committed by humanitarian personnel themselves. In a 2022 report conducted by the UN in South Sudan and sent to humanitarian agencies, residents said sexual exploitation, mostly perpetrated by humanitarian workers, was being experienced “on a daily basis.” Women and girls assaulted by aid workers often fear reporting because it could affect food rations and other services provided by the perpetrator’s organization. In fact, most reporting is from women humanitarian aid workers who have been assaulted by colleagues. Consensual relationships between residents and aid workers are also banned, as it is considered an abuse of power. To combat this, humanitarian organizations have conducted education campaigns and held talks on reporting with the community, broadcasted messages over the radio, and shared a hotline number to raise awareness. Yet, women in refugee camps are still escaping one harsh reality to move into another.

Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Refugee Camps

One in five displaced refugee women experience sexual violence in refugee camps, environments where their wellbeing and safety should be secured. In refugee camps, one of the most prevalent forms of SGBV is intimate partner violence (IPV), which is behavior used to maintain control over a partner, including physical, sexual, emotional, economical, or psychological action or threat of action. IPV rates increase when external stressors lead to concerns over livelihood, food, shelter, and other resources, and results in a “loss of power” for men, leading to violent coping mechanisms. COVID-19 and drought are prominent stressors, with one report indicating that just seven months after the pandemic started, 73 percent of women reported an increase in IPV and 51 percent a rise in sexual violence. Similarly, in 2022 alone, over 400 women and girls sought SGBV services in Kenya’s Dadaab refugee camp as the region faced its fifth failed rainy season; this figure is likely higher given underreporting.

A lack of community support increases the likelihood of IPV, and measures to protect against it largely depend on survivors reporting the incident. In some Kenyan and Somali tribes, community elders determine the veracity of IPV, as it is seen as a marital issue that can signify affection rather than a violation of the survivor’s rights. Humanitarian organizations are addressing these cultural norms through focus group discussions involving men, women, and community elders, and through women’s shelters that provide safe spaces for survivors. While the discussions confront stigmas around reporting and seek to educate audiences about the harm of IPV, there is often a lack of buy-in. Furthermore, since the identity of survivors who enter women’s shelters are not anonymous, there is limited protection and security to those viewed to be defying cultural expectations.

Another common form of violence against women and girls in refugee camps is child marriage, defined as a formal marriage or informal union between a child under the age of 18 and an adult or another child. Despite being illegal in Kenya since 2001, there are reports of families arranging to marry girls as young as 12 to men more than five times their age. Rising in tandem with child marriage are rates of female genital mutilation (FGM), an illegal procedure that is a prerequisite for marriage in many communities, which involves the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. Both banned acts have spiked in recent years with the continuation of drought and COVID-19, illustrating that in times when resources are stretched untenably thin, girls are commodified, often for the family’s survival. As the drought continues, dowries, or payment to the bride’s family, decrease as grooms have less to offer, making the wait for the girl to enter adulthood financially unsustainable for the family. Child marriages result in a higher vulnerability to domestic violence, IPV, and a lifetime of poverty as girls likely have not completed their education and are economically dependent on their husbands.

While child marriages are rising, female genital mutilation is also being perpetuated by cultural norms that consider virginity to be a virtue and inextricable from family honor. Many girls who refuse to undergo FGM are considered to be “stealing” from their families and are often labeled as “contaminants” who cannot use the community well. FGM also provides a substantial income for displaced women who conduct the procedure, creating an economic incentive to allow the practice to continue. One Kenyan chief noted that “no one will even negotiate a bride price for uncut girls,” highlighting the economic value placed on the practice.

For decades, humanitarian organizations have implemented protection programming to address child marriage and FGM. However, it is not entirely effective due to the unpredictability of the climate and conflict events that exacerbate violence against women and girls, and the fact that as external actors, it is difficult to intervene in ingrained cultural practices. Additionally, these organizations must focus on providing food, water, and life-saving assistance, which pushes combatting child marriage and FGM down their list of priorities.

A Loss of Livelihood

A loss of livelihood usually accompanies crises and forced displacement and presents several protection risks for women and girls. Women are often excluded from decision-making as well as control of resources and assets at the family and community level. This exclusion makes it significantly more difficult for women and girls to handle shocks and pressures them to adopt negative coping mechanisms that provide short-term solutions while reducing their ability to rebuild livelihoods in the medium and long term.

One of these coping strategies is selling resources to meet basic needs. While this strategy staves off immediate threats, it becomes harmful in protracted situations as people are compelled to sell assets essential for their livelihoods, including livestock and land. Women benefit even less from this strategy than men as they control fewer resources, if any at all, and men often control the profits that come from selling assets. A lack of access to and control over resources, coupled with a lack of legal recognition of the right to work in the host country, drives women into exploitative working conditions where they are often subjected to discrimination and sexual violence. Humanitarian organizations provide work opportunities for women, but the amount of women in need of employment requires a larger, more systemic change that builds upon underutilized and healthy coping strategies.

Risks to youth, particularly girls, also increase as children are forced into exploitative working conditions alongside their parents in sectors such as agriculture and waste recycling. If girls are not working, they are married off as desperate parents seek ways to reduce the burden of care and provide for their families. Unfortunately, both child labor and child marriage occur at higher rates in female-headed households given that resources and opportunities for women are lower and given that working and married children cannot access education, their livelihood opportunities are further reduced.

Lack of access to education and employment creates significant protection issues for communities and humanitarian organizations due to the presence of extremist groups. Girls lack educational opportunities at a disproportionate level compared to boys because families prioritize boys’ education due to cultural norms which devalue girls’ education and social mobility. Meanwhile, some families refuse to send girls to school out of fear of sexual violence. Youth with few opportunities for education or employment are more vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups, which Dadaab camp residents label an “omnipresent” issue. And while men are perceived as the main perpetrators of violent extremism, a closer examination shows that young women are increasingly involved in violent attacks due to their disproportionate lack of opportunities.

Protection gaps in camps also abound when it comes to healthcare. Reduced livelihoods, lack of access to resources, and the lack of opportunities for fair and dignified work force women to skip or reduce their meals to feed the men and children in their families. Female-headed households suffer from this issue more than male-headed households as they must choose between food security and other necessities such as medicine and fuel. Food insecurity and inadequate nutrition further compound the increased risks that women face.

Humanitarian organizations in refugee camps recognize and work to address the gendered issues that women and girls face when attempting to rebuild and strengthen their livelihoods and significant improvements have been made. Psychosocial support, referral pathways, safe spaces for survivors of SGBV, and Village Savings and Loans Associations for women and female-headed households strengthen their livelihoods and have led to demonstrable benefits. However, these interventions fail to address the underlying issues that create situations of insecurity. Long-term solutions that support women and girls in building sustainable livelihoods and investing in their futures must be prioritized by the national government and humanitarian organizations.

Understanding the Policy Landscape

Forced displacement in the Horn of Africa and its impact on women and girls is a transnational issue that requires cooperation across host countries with strong support from the international community. While there are frameworks intended to protect women and girls from violence and help them realize their full economic potential, they are difficult to put into practice. This can be attributed to intergovernmental tensions and the extremely limited scope of applicable policies regarding refugee camps in international frameworks.

At the international level, there is the 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, the 2008 UNHCR Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls, and the 2011 UNHCR strategy tackling SGBV. These frameworks are intended to address, directly or indirectly, the culture of neglect and denial about violence against women and girls and advocate for gender equality. In addition to codified mandates, humanitarian aid workers have a duty of care to the beneficiaries of their services, which has been made clear in the “Do No Harm” approach and the UN secretary-general’s statement on zero tolerance for sexual exploitation and abuse. Unfortunately, these frameworks and measures have seen limited success. While they provide guiding principles, contextualizing them in refugee camps in East Africa requires investments in practical structures, social and behavior changes, and institutions.

At the national governmental level, Kenya and Somalia have been at odds in their responses leading to fragmented solutions. The 2021 Refugee Act has the potential to improve the inclusion and integration of refugees in Kenya; however, the details and implications of certain provisions remain unclear. The law states that refugees, “shall have the right to engage individually or in a group, in gainful employment or enterprise or to practice a profession or trade where he holds qualifications recognized by competent authorities in Kenya.” However, lack of documentation remains a significant challenge for displaced people who are unable to leave designated areas. If these areas remain restricted to camps and reception areas then refugees, especially women, will struggle to take full advantage of business and employment opportunities. And while the Act does allow for displaced people from the East African Community (EAC) to give up their refugee status and apply for a work permit, the majority of the refugees in Kenya are from Somalia which is not a member of the EAC.

Accounting for refugee returns is part of a holistic refugee policy framework. In recent years, Somalia has formulated the National Policy on Refugees-Returnees and IDPs, which aims to provide protection and durable solutions for refugees and IDPs through voluntary return, local integration, and permanent relocation. It also focuses on the special needs of women and children, as well as other vulnerable populations. However, disputes over land remain a significant obstacle for proper implementation and protection of IDPs and refugees. While the Interim Protocol on Land Distribution for Housing to Eligible Refugee-Returnees and IDPs has attempted to overcome these obstacles by preventing arbitrary eviction and allocating land to vulnerable groups, Somalia’s conflict-affected condition and fragmented governance system prevent the full realization of these policies.

The complex nature and rising levels of displacement in East Africa exacerbates pre-existing vulnerabilities for women and children, necessitating multi-level cooperation on client-informed security, migrant protection, and development policies to ensure their protection.

Policy Solutions

Governments, humanitarian actors, local authorities, and development actors must prioritize meaningful interventions that address the gendered impact of protracted displacement contexts. These include embedding permanence in the architecture of camps, conducting education campaigns against SGBV, providing economic incentives for keeping girls in school, offering livelihood training, and fully implementing the 2021 Refugee Act. Most importantly, the design and implementation of such solutions must be led and informed by the people they are meant to address.

Refugee camps are designed to meet basic needs and are therefore built as temporary solutions to long-term displacement crises. Consequently, they are not equipped with the necessary infrastructure, including staff and facilities, to support the safety of women and girls. Camp designs must move away from “refugee warehousing” towards a resident needs-centered approach. This involves embedding permanence in the spatial configuration of camps while recognizing that transiency might better reflect the aspirations of stakeholders involved. Permanence can take the form of socio-economic integration like the Kalobeyei settlement where architectural plans include a market and shared public services between refugees and the indigenous Turkana hosts. It can also take the form of hiring more women incentive staff—refugees employed by NGOs—which contributes to the sustainability of protection programs for women and girls. The construction of more permanent, centralized facilities not only fosters a sense of belonging, but also decreases the likelihood of women and girls experiencing sexual and gender-based violence.

To address systemic SGBV, NGOs should partner with local organizations, like the Kenya-based Samburu Girls Foundation, to campaign and educate girls, women, and men about the risks associated with intimate partner violence, child marriage, and female genital mutilation, as well as methods of preventing their occurrence, and how to address them when they do. Local governments must also actively engage community leaders, such as village elders, to ensure that national laws that ban forms of SGBV are brought to the community level. To address the economic incentives associated with SGBV, NGOs should initiate programming that encourages keeping girls in schools and disincentivizes FGM and child marriage. This means providing families with the option of cash assistance to replace a potential dowry and is contingent on the girl staying in school. Relatedly, FGM practitioners should be deterred from carrying out the practice by offering trainings that reskill them for other means of livelihood.

Thirdly, Kenyan national policies such as the 2021 Refugee Act should be codified and enacted to allow refugees to pursue livelihoods outside of temporary camp settings. This includes official registration, access to documentation, and skill-set recognition to ensure that clients can access livelihoods that reaffirm their dignity. This will not only assist women and girls in protecting their autonomy but will also discourage boys and men from joining extremist groups.

Neglect and protection issues are not always the baseline in camp settings, but they become the norm when international, national, and NGO policies do not adequately converge and especially when they leave women and girls out of the decision-making process. Humanitarian efforts must recognize that women and girls have much to contribute to preparing for, and responding to, crises. This is imperative because women and girls’ involvement could positively affect their access to services, self-reliance, capacity for economic inclusion, and ultimately, their protection.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies(SAIS) or the SAIS Foreign Policy Institute.

Works Cited

“Situation Regional Bureau for the East and Horn of Africa, and the Great Lake Region,”2022, UNHCR, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/rbehagl.

“Women and Girls Account for the Majority of Migrants in East and Horn of Africa: IOM Report,” United Nations International Organization for Migration, September 7, 2022, https://www.iom.int/news/women-and-girls-account-majority-migrants-east-and-horn-africa-iom-report.

“Somalia: Internal Displacement-UNHCR Operational Data Portal,” UNHCR, 2023, https://data.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/1?sv=1&geo=192.

“Horn of Africa Drought Leading to Increasing Violence Against Women and Girls,” International Rescue Committee, 2022, https://www.rescue.org/press-release/new-irc-data-horn-africa-drought-leading-increasing-violence-against-women-and-girls.

“What is a Refugee Camp?” USA for UNHCR, https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/camps/.

Amber Aubone and Juan Hernandez, “Assessing Refugee Camp Characteristics and the Occurrence of Sexual Violence: A Preliminary Analysis of the Dadaab Complex,” Refugee Survey Quarterly, 32, no. 4 (2013): 22-40, https://www.jstor.org/stable/45054915.

Linda Merieau and Amara Gebere Egyziaber, “Light Years Ahead: Innovative Technology for Better Refugee Protection,” UNHCR, 2012, https://www.humanitarianlibrary.org/sites/default/files/2014/03/Light%20years%20ahead%20UNHCR.pdf.

Shima Bahre, “How the Aid Sector Marginalises Women Refugees,” The New Humanitarian, March 15, 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/first-person/2021/3/15/How-the-aid-sector-marginalises-women-refugees.

“Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action,” United Nations Inter-agency Standing Committee, August 29, 2015, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/guidelines-integrating-gender-based-violence-interventions-humanitarian-action-reducing.

Sam Mednick and Joshua Craze, “Alleged Sex Abuse by Aid Workers Unchecked for Years in UN-run South Sudan Camp,” The New Humanitarian, September 22, 2022, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/2022/09/22/exclusive-alleged-sex-abuse-aid-workers-unchecked-years-un-run-south-sudan-camp.

Sophie Edwards, “Sexual Assault and Harassment in the Aid Sector: Survivor Stories,” Devex, February 7, 2017, https://www.devex.com/news/sexual-assault-and-harassment-in-the-aid-sector-survivor-stories-89429.

“Violence Prevention and Response at the International Rescue Committee,” International Rescue Committee, October 12, 2016, https://www.rescue.org/resource/violence-prevention-and-response-international-rescue-committee.

Alexander Vu et al, “The Prevalence of Sexual Violence Among Female Refugees in Complex Humanitarian Emergencies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” National Library of Medicine, March 18, 2014, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24818066/.

“New Report Finds 73% of Refugee and Displaced Women Reported an Increase in Domestic Violence Due to COVID-19,” International Rescue Committee, October 15, 2020, https://www.rescue.org/press-release/new-report-finds-73-refugee-and-displaced-women-reported-increase-domestic-violence.

Yonas Gebreiyosas, “Gender-Based Violence Against Female Refugees in Refugee Camps: Case of Mai Ayni Refugee Camp, Northern Ethiopia,” GRIN, 2013, https://www.grin.com/document/212288.

“Child Marriage on the Rise in Horn of Africa as Drought Intensifies,” UNICEF, June 28, 2022, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/child-marriage-rise-horn-africa-drought-crisis-intensifies.

Daniel Howden, “Kenyan ‘Cutter’ Says Female Genital Mutilation is Her Livelihood,” February 7, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/feb/07/female-genital-mutilation-kenya-daughters-fgm.

“Integrating a Gender Perspective into Statistics,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Capacity Development, 2015, https://www.un.org/development/desa/cdpmo/tools/2020/integrating-gender-perspective-statistic.

Awa Mohamed Abdi, “Refugees, Gender-Based Violence and Resistance: A Case Study of Somali Refugee Women in Kenya,” in Women, Migration and Citizenship, ed. Evangelia Tastsoglou and Alexandra Dobrowolsky(London:Routledge, 2016), https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315546575-11/refugees-gender-based-violence-resistance-case-study-somali-refugee-women-kenya-awa-mohamed-abdi.

“Doing Business in Dadaab, Kenya,” International Labour Organization, May 2, 2019, https://www.ilo.org/empent/Projects/refugee-livelihoods/publications/WCMS_696142/lang–en/index.htm.

“UNHCR Operational Update-Dadaab, Kenya, June 2019,” UNHCR, June 30, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/unhcr-operational-update-dadaab-kenya-june-2019.

“Welcoming Newcomers to CVT’s Work in Dadaab,” The Center for Victims of Torture, February 25, 2016, https://www.cvt.org/blog/healing-and-human-rights/welcoming-newcomers-cvt%E2%80%99s-work-dadaab.

Mozeda Hossain and Chimaraoke Izugbara, “Violence, Uncertainty, and Resilience Among Refugee Women and Community Workers: An Evaluation of Gender-Based Violence Case Management Services in the Dadaab Refugee Camps,” Care International/International Rescue Committee, February 2018, https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/publications/violence-uncertainty-and-resilience-among-refugee-women-and-community-workers-an-evaluation-of-gender-based-violence-case-management-services-in-the-dadaab-refugee-camps.

“Policy Brief: Gendered Vulnerabilities and Violent Extremism in Dadaab,” United Nations Kenya, 2020, https://www.genderinkenya.org/publication/policy-brief-gendered-vulnerabilities-and-violent-extremism-in-dadaab/.

“Safe Access to Fuel and Energy (SAFE),” World Food Programme, August 1, 2019, https://www.wfp.org/publications/safe-initiative.

“Accessing Finances Through Village Savings and Lending Associations in Kenya,” 50 Million African Women Speak, 2017, https://www.womenconnect.org/web/kenya/vslas.

Rosa da Costa, “The Administration of Justice in Refugee Camps: A Study of Practice,” UNHCR, March 2006, https://www.unhcr.org/protection/globalconsult/44183b7e2/10-administration-justice-refugee-camps-study-practice-rosa-da-costa.html.

“Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, December 20, 1993, https://previous.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ViolenceAgainstWomen.aspx.

“UNHCR Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls,” UNHCR Division of Internal Protection Services, March 6, 2008, https://www.unhcr.org/protection/women/47cfae612/unhcr-handbook-protection-women-girls.html.

“Action Against Sexual and Gender-Based Violence: An Updated Strategy,” UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, June 30, 2011, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/action-against-sexual-and-gender-based-violence-updated-strategy.

“Collective Statement of the Members of the Secretary-General’s Circle of Leadership on the Prevention of and Response to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in United Nations Operations,” United Nations, 2021, https://www.un.org/preventing-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse/content/collective-statement-members-secretary-general-circle-leadership.

“Act No. 10: Refugees,” Government of Kenya, 2021, https://ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=112960.

“Somalia Launches First Policy on Displaced Persons, Refugee-Returnees,” International Development Law Organization, December 17, 2019, https://www.idlo.int/news/somalia-launches-first-policy-displaced-persons-refugee-returnees.

“Interim Protocol on Land Distribution for Housing to Eligible Refugee-Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons,” Federal Government of Somalia, 2019, https://www.refworld.org/country,,,,SOM,,5d8331024,0.html.

“Kalobeyei Settlement,” UNHCR, https://www.unhcr.org/ke/kalobeyei-settlement.