The emergence of China as an international lender has changed the landscape of global development finance. Since the early 2000s, the Chinese government and its state-owned banks have provided record amounts of loans to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), making China the world’s largest official creditor.1 China’s lending has challenged the Paris Club hegemony, surpassing that of all its members combined.2

This paper examines a specific but crucial area of China’s increasing investments in transition minerals- key materials essential for energy transition. These minerals, concentrated in developing economies with weak regulatory frameworks, have attracted substantial Chinese investments. Various explanations have been proposed for this trend, including domestic political motives, supply chain disruptions post-pandemic, rising demand, and China’s strategy to dominate global green technology supply chains.3 However, the lack of transparency in China’s lending practices and the confidentiality of state-owned enterprise (SOE) contracts make it difficult to discern Beijing’s precise intentions.4

China’s rapidly expanding investment in transition minerals is vital for the global economy, especially in the current era of energy transition. However, this has sparked concerns among developed nations and major emerging market economies striving to achieve their energy transition objectives. While greater investment in exploration and mining can increase supply and potentially decrease prices, China’s near-monopoly on refining and production creates the risk of price manipulation and energy security vulnerabilities.5

Additionally, the rise of Chinese bilateral financing has serious implications for debtor nations. A higher share of Chinese debt in debtor countries’ national portfolios has been linked to fiscal distress, increased corruption, economic distortions, and the erosion of private procurement laws, granting governments greater fiscal flexibility to allocate funds at their discretion.6

The Role of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Since its launch in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been a critical turning point in China’s overseas economic engagement. Scholars offer conflicting views on its objectives; some argue that it was designed to expand trade routes and infrastructure investments, creating mutually beneficial cooperation and projecting power abroad, while others see it as a strategic narrative aimed at offsetting China’s domestic economic challenges.7,8,9

Ultimately, the BRI served as a strategic umbrella, allowing Chinese SOEs to undertake projects and investments in countries that would have previously triggered international scrutiny.10 By leveraging opaque financing mechanisms, China has expanded its influence under the guise of “win-win” partnerships.

The introduction of the BRI coincided with the rise of long-term, relational credit often referred to as “Patient Capital.”11 This type of financing, spearheaded by Chinese policy banks, benefits from state financial backing, implicit subsidies, weaker financial oversight, a high national savings rate, and the government’s implicit backing of their overseas lending.12

This paper investigates how China’s investment strategy in transition minerals has evolved post-BRI introduction, facilitated by the emergence of “patient capital.” We hypothesize that the introduction of the BRI in 2013, combined with the rise of “patient capital” after 2008, has fundamentally altered China’s approach to transition mineral investments, transforming high-risk, commercially unviable projects into state-backed strategic assets. This shift has enabled China to bypass traditional global diplomatic scrutiny, secure long-term control over critical mineral supply chains, and strengthen its geopolitical influence under the guise of economic cooperation.

China’s ability to fund high-risk, long-term projects, particularly in transition minerals, has been significantly enhanced under the BRI framework. Previously deemed too risky, large-scale mine acquisitions and infrastructure projects are now bankrolled through state-backed financing, enabling China to expand its influence in resource-rich developing countries. Given the highly capital-intensive nature of the mining sector, which demands substantial upfront investments and recurring expenditures, China’s access to large-scale credit has effectively lowered entry barriers. This has allowed Chinese firms to secure long-term control over critical transition mineral supply chains, further consolidating the country’s dominance in the global green technology sector.13 This research examines the extent, nature, and consequences of this shift, highlighting its implications for debtor nations and global supply chain security.

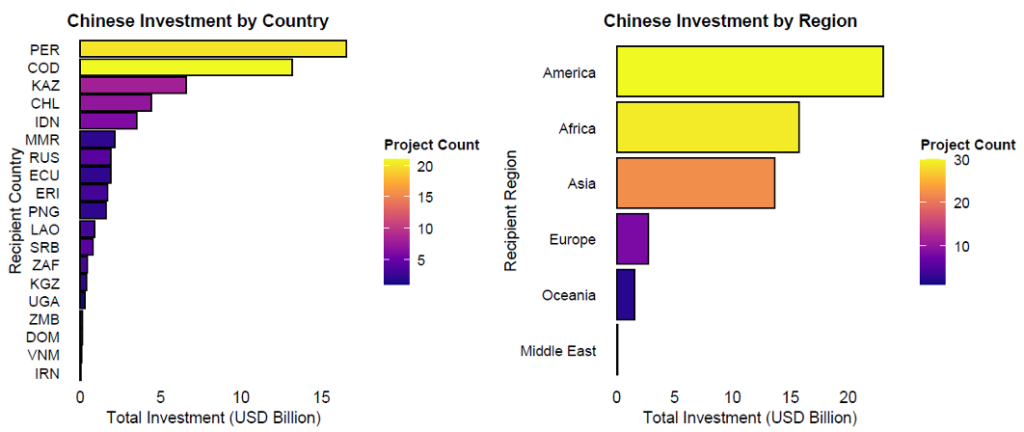

Flow of funds and projects across countries14

While much attention has been paid to China’s influence in Africa, credit flows to Latin America have been largely overlooked. Africa and Latin America are major recipients of Chinese funding for transition minerals projects, primarily due to their large mineral reserves. Peru and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have emerged as major recipients of Chinese investment in transition minerals, with over 20 projects in the past two decades. A significant portion of these investments is concentrated in the upstream mining segment, which remains China’s weakest link in the supply chain. While China has already established dominance over midstream and downstream segments, securing control over upstream extraction is a strategic move to strengthen its grip on the entire transition minerals supply chain.15

China’s dominance raises concerns about its near monopoly in these countries. Western countries struggle to compete at the same scale due to environmental concerns, slow bureaucratic processes, profitability concerns, and difficulty in accessing credit.16 This also raises concern over the internal debt dynamics of these nations and emerging macroeconomic growth models.

Figure 1: Distribution of China’s projects and investments over countries and regions. (Note: The investment is in USD Billion, 2021 constant.) Data sourced from AidData.

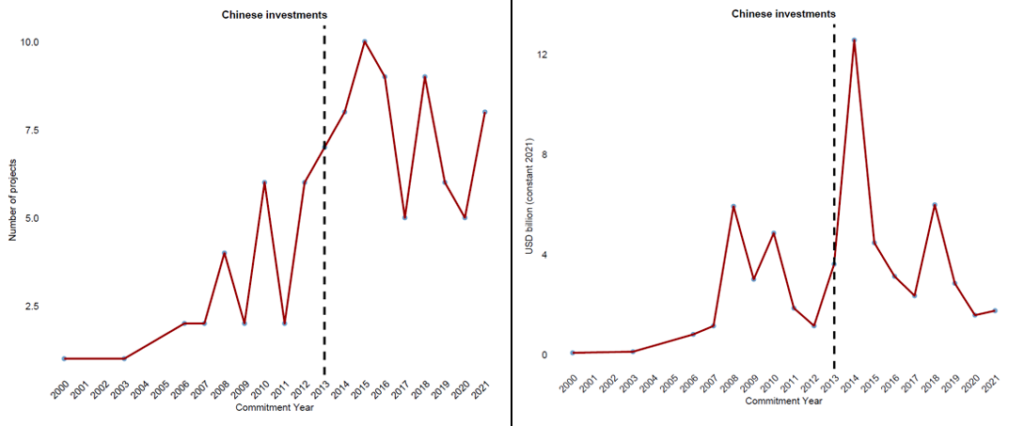

Quantifying the Impact of BRI on Investment Patterns

China has been an early mover in the market17 and was investing in transition minerals well before the launch of the BRI, but a significant uptick was observed post-2013. This strong jump was needed to signal a bold commitment to create the rhetoric of mutual prosperity and development and overcome domestic and global pressures. Further, many projects that had commenced earlier were later rebranded under the BRI framework, resulting in a sudden surge in projects and investment in 2013.18 While official financial commitments may appear to have declined post-2014, this is largely a statistical artifact, as investments are recorded entirely in the commitment year rather than being distributed across the project’s duration.19 However, when funding flows are adjusted to reflect the actual timeline of project implementation, Chinese investment in transition minerals remains relatively stable post-BRI, reinforcing the long-term nature of its resource acquisition strategy.

Figure 2: Trends in Transition Mineral Project Numbers and Investment Flows Over Time. Data sourced from AidData.

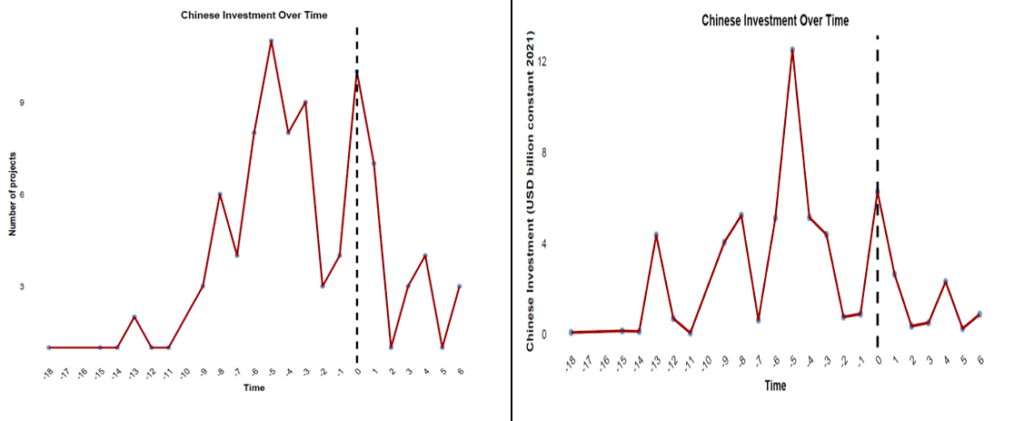

Impact on countries joining the BRI

As suggested above, the surge following the BRI announcement in 2013 was to solidify its dominance and was also a statistical artifact, as many pre-BRI projects were also categorized under the BRI banner. To assess whether joining the BRI led to increased project announcements and investment, an event study approach is deployed. Each country’s year of signing the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) and joining the BRI was normalized as Year 0, allowing for a comparative analysis of investment trends before and after entry.

Figure 3: Trends in Transition Mineral Project Numbers and Investment Flows Pre and Post joining BRI. Data sourced from AidData.

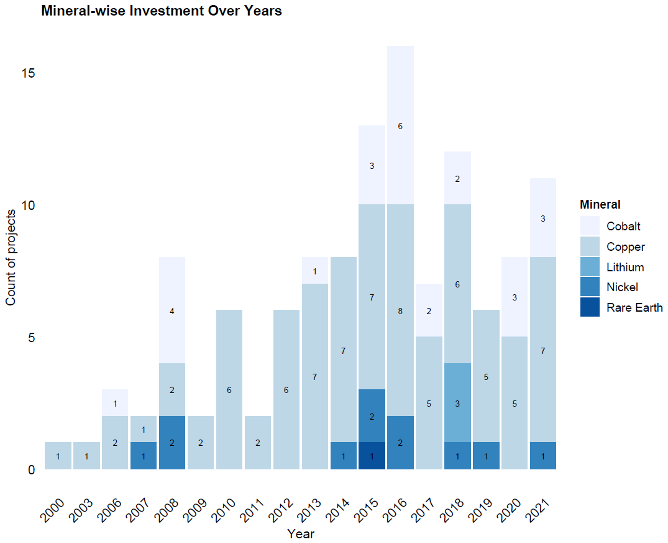

Change in investment playbook post-BRI

The introduction of BRI not only altered the flow of investment funds and the volume of announced projects but also led to a fundamental shift in China’s overall investment strategy. A noticeable change has emerged in the key transition minerals attracting Chinese investments, reflecting a more targeted approach to securing resources critical for the global energy transition. While pre-BRI projects were largely centered on copper mining, post-2013 investments show a pivot toward cobalt, lithium, and nickel, minerals that have gained increasing importance due to their role in battery production and clean energy technologies. In contrast, Rare Earth Elements (REEs) remain a lower priority, as China already holds 35% of the global REE mineral reserves, thereby reducing the need for aggressive overseas acquisitions in this segment.20

Figure 4: Transition minerals attracting investment over time. Data sourced from AidData.

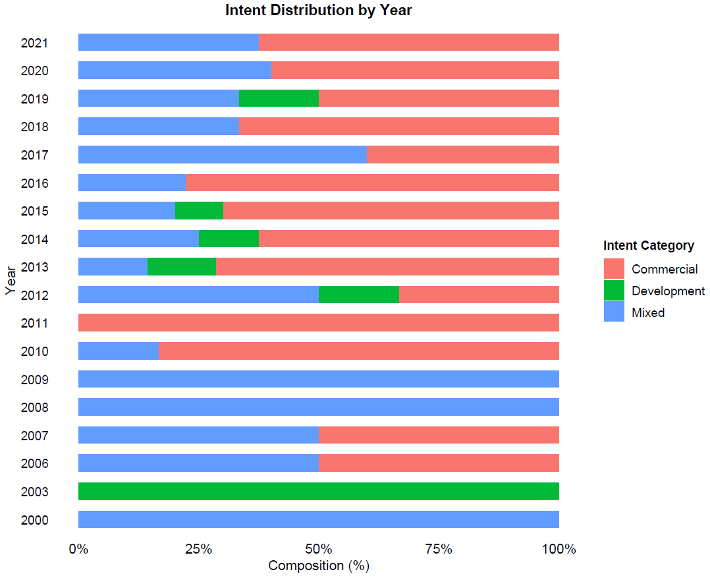

Analyzing project descriptions alongside data on variables such as grant components and interest rates, AidData captures the intent of each project. While Chinese projects have traditionally been driven by mixed objectives (combining development and commercial goals), there has been a notable increase in the prevalence of projects with primarily commercial objectives in recent years.

Figure 5: Trend in Intent for undertaking the mining projects. Data sourced from AidData.

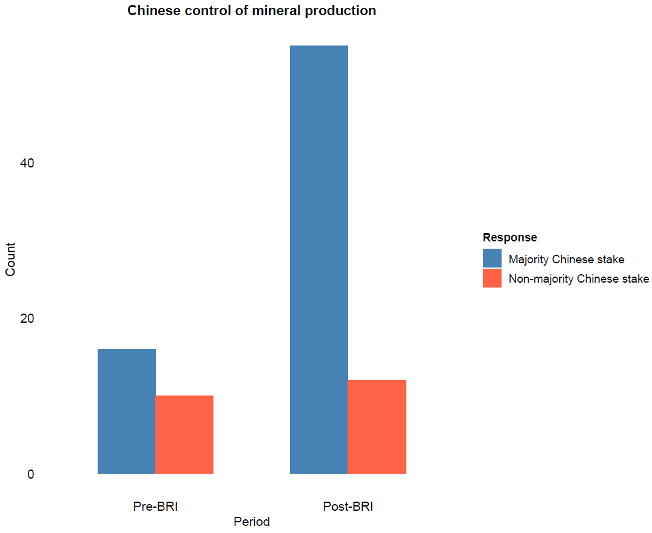

Post BRI, China has been increasingly taking majority ownership in the transition minerals projects. The proportion of projects with Chinese majority ownership has surged. Moreover, heavy reliance on commodity exports heightens vulnerability to fluctuations in global prices, undermining these countries’ ability to manage debt sustainably. Additionally, the intensified extraction of natural resources risks exacerbating economic inequalities, fostering corruption, and fueling instability and conflict across debtor countries.21

Figure 6: Chinese stake in mineral projects. Data sourced from AidData.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

As global economic transformations accelerate, securing access to transition minerals will be a defining factor in shaping geopolitics in the coming years.22 The increasing concentration of supply chains in China presents a significant risk to global energy security, as geopolitical tensions or even logistical disruptions could severely impact the availability of transition minerals.23 To ensure a resilient and diversified supply chain, it is imperative to reduce dependency on China and expand resource development efforts in LMICs.

Given the capital-intensive and high-risk nature of mining projects in LMICs, private sector investment alone is insufficient. Without strong state-backed financing mechanisms, companies will be reluctant to enter these markets. To effectively challenge China’s hegemony, developed economies need to design competitive financing arrangements that appeal to the developing economies while limiting restrictive policy conditionalities.24

Capital, particularly in Africa and South America, to counter Beijing’s strong economic and diplomatic foothold. However, challenging China’s soft power in these regions will not be easy, especially in light of recent US foreign aid cuts that have weakened Western influence.

Without decisive action, China’s near monopoly over transition minerals will continue to shape the global energy landscape, reinforcing its strategic control over critical supply chains for decades to come.

References

[1] Anna Gelpern et al., “How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments,” AidData, March 31, 2021, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/how-china-lends.

[2] Sebastian Horm et al., “China’s Overseas Lending,” Working Paper 26050, 2019, http://www.nber.org/papers/w26050.

[3] Rodrigo Castillo and Caitlin Purdy, “China’s Role in Supplying Critical Minerals for the Global Energy Transition: What Could the Future Hold?” Brookings, August 1, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-role-in-supplying-critical-minerals-for-the-global-energy-transition-what-could-the-future-hold/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Stephen B. Kaplan, Globalizing Patient Capital, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316856369.

[7] Mykyta Simonov, “The Belt and Road Initiative and Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment: Comparison and Current Status,” Asia and the Global Economy 5, no. 1 (February 13, 2025): 100106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aglobe.2025.100106.

[8] “Interview: China’s Belt and Road Initiative Offers ‘Win-win Solutions’ to Nations, Says Turkish Expert,” n.d. https://english.news.cn/20241225/1fa2e0bac4d7463fbd3a79bafbbc92dd/c.html#:~:text=ANKARA%2C%20Dec.,Xinhua%20in%20a%20recent%20interview.

[9] Min Ye, The Belt Road and Beyond, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108855389.

[10] Jacque Schrag, “How Is the Belt and Road Initiative Advancing China’s Interests?” ChinaPower Project, October 11, 2024, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Brooke Escobar et al., Power Playbook: Beijing’s Bid to Secure Overseas Transition Minerals, AidData, 2025, https://docs.aiddata.org/reports/china-transition-minerals-2025/FULL_REPORT_Power_Playbook.pdf.

[14] To test this hypothesis, we use data from AidData, an international development research lab, housed at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, the only reliable source tracking granular Chinese lending. The dataset covers five transition minerals: Copper, Cobalt, Nickel, Lithium, and Rare Earth Elements in 19 countries, capturing 93 Chinese loan commitments over the period 2000–2021. This study adopts a descriptive-analytical approach to assess the impact of the BRI on Chinese lending. It employs graphical representations and trend analysis to derive meaningful insights from the dataset. Additionally, an event study approach is utilized in a later section to evaluate the impact of joining the BRI on individual countries.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains: An Action Plan Developed in Response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017 – Defense Management Institute,” n.d., https://www.dmi-ida.org/knowledge-base-detail/An-Action-Plan-Developed-in-Response-to-President-Bidens-Executive-Order-14017.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Jonathan E. Hillman, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later,” October 28, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-five-years-later.

[19] Ibid.

[20] International Energy Agency, “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024 – Analysis – IEA,” May 1, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2024.

[21] Edward A. Burrier and Thomas P. Sheehy, “Challenging China’s Grip on Critical Minerals Can Be a Boon for Africa’s Future,” United States Institute of Peace, June 7, 2023.

[22] Sophia Kalantzakos, “The Race for Critical Minerals in an Era of Geopolitical Realignments.” The International Spectator 55, no. 3 (July 2, 2020): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2020.1786926.

[23] Rodrigo Castillo and Caitlin Purdy, “China’s Role in Supplying Critical Minerals for the Global Energy Transition: What Could the Future Hold?” Brookings, August 1, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-role-in-supplying-critical-minerals-for-the-global-energy-transition-what-could-the-future-hold/.

[24] Ibid.