In an era marked by unprecedented global connectivity and interdependence—regional collaborations, especially those structured around institutions, play a pivotal role in shaping the geopolitical and geo-economic landscape. The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) stands poised at the crossroads of strategic importance and untapped economic potential. The initiative was heralded at the time for initiating the development of a web of relations among the nations nestled in the lap of the Bay of Bengal. To what extent has it proved its advocates, believers, and even critics correct? This piece takes a deep dive into the region to uncover the successes and failings of BIMSTEC. We will also provide a series of recommendations that BIMSTEC nations should consider to reignite the fading embers of integration.

BIMSTEC: The Enigma

Encompassing nations bordering the Bay of Bengal—Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand—BIMSTEC seeks to foster economic development, technological cooperation, and cultural exchange among its members. A product of India’s “Look East ” and Thailand’s “Look West” policy, BIMSTEC sought to connect South Asia with Southeast Asia. To do so, it ascribes particular issue domains to individual member nations, such as Bhutan – environment, India- non-traditional security threats, and Thailand on the issue domain of connectivity. Despite a clear division of responsibility, it took 25 years for BIMSTEC to develop a Charter. BIMSTEC’s primary goal according to it, is to create an enabling environment for rapid economic growth among its constituents. A good proxy to identify the degree of economic interconnectedness and growth is to examine the degree of intra-regional trade and investment.

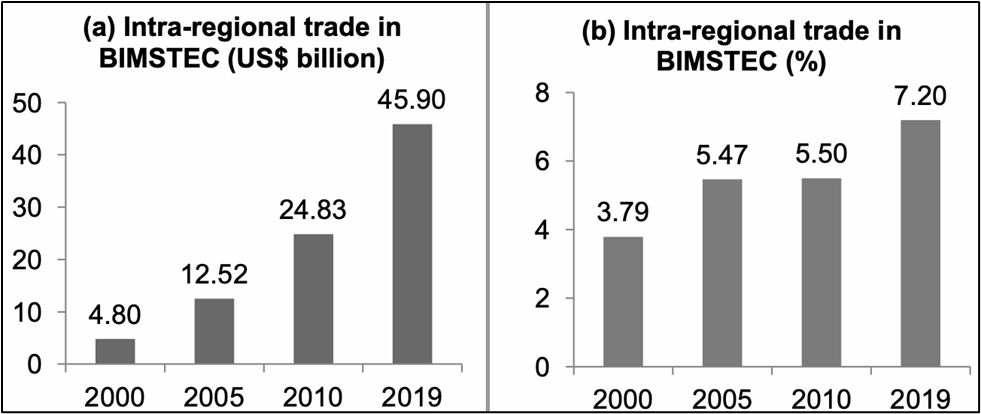

Intra-regional trade and investment flows, however, fall short of expectations. Within BIMSTEC, a burgeoning infrastructure investment gap of approximately $120 billion annually, poses a looming challenge. While there have been improvements in metrics such as physical connectivity and the volume of intra-regional trade, the improvement over time has been dismally slow, with intra-regional trade hovering at a mere seven percent (See image 1 below). While this remains higher than the intra-regional trade between SAARC nations (at less than five percent), it remains much lower than its neighbor ASEAN (at approximately twenty-five percent).[1] As the infrastructure gap widens, BIMSTEC’s journey toward seamless economic collaboration demands a holistic and strategic approach toward economic integration. The triangulation of digital connectivity, transport connectivity, and people-to-people connectivity is particularly imperative to deal with the challenges of the 21st Century.

For BIMSTEC to thrive as a regional institution, external assistance is also required. The organization should tap into its partnership with international organizations such as the Asian Development Bank, and partners like the United States and Japan, as well as collaborate with private entities to access financial resources and technical expertise that can facilitate mutually beneficial cross-border initiatives. As an initial step—in November 2022 BIMSTEC partnered with the Asian Development Bank to develop the BIMSTEC Trade Facilitation Strategic Framework 2030 which outlines constraints and the progress made by the BIMSTEC economies at promoting growth in the evolving trade environment.[3] Even so, to realize the objectives set out in the framework, India needs to play a pivotal role.

India: The Reluctant Leader

BIMSTEC, like other regional organizations such as the European Union and ASEAN, needs a leader; one who remains willing and able to take up the mantle of leadership. Thus far, however, India has been somewhat ambivalent in the global economic domain. Despite undertaking several rounds of negotiation on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), India withdrew from the bloc citing concerns about the potential impact on its economy.[4] India also opted out of the trade pillar negotiations for the US-led Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF).[5] These developments does not augur well for the fate of the BIMSTEC FTA, which has been paraded as a key objective of the organization for several decades but remains beyond reach.

Regional economic free trade agreements (FTA) often need a driver behind the wheel. The RCEP, which came into force in 2022, was driven by ASEAN.[6] After the US pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Japan took the lead to revive it with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).[7] Even in the case of the now seemingly dead SAARC, India and Pakistan’s leadership played a pivotal role in realizing the South Asian Preferential Trade Arrangement (SAPTA) in 1995 and the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) in 2004.[8] In the backdrop of the ASEAN FTA, the CPTPP, and the RCEP FTA, BIMSTEC’s failure to actualize an FTA appears even more disappointing.

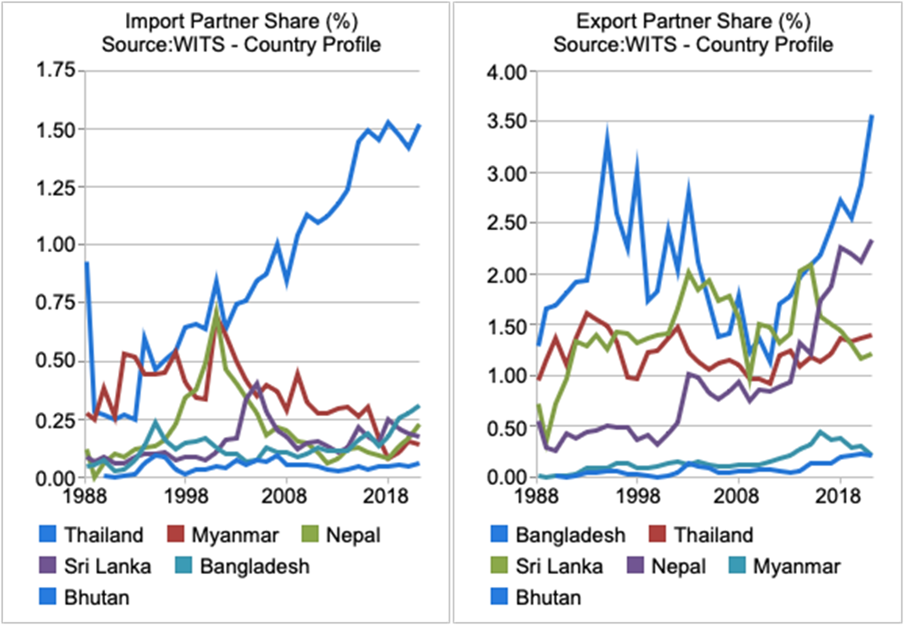

Despite its position as one of the top 10 economies of the world based on GDP estimates, India’s trade volume with other BIMSTEC nations remains abysmally below five percent in both imports and exports, as reflected by the images below (Images 2 and 3). Nevertheless, opportunities for cooperation exist and, if harnessed effectively, can lead to significant growth over the medium and long term.

| Image 2 (left) – India Import Partner Share by country in percentage 1988-2021 Source: World Bank World Integrated Trade Solution. | Image 3 (right)- India Export Partner Share by country in percentage 1988-2021 Source: World Bank World Integrated Trade Solution. |

Opportunities for Cooperation

Firstly, the need for an FTA is manifestly evident. If the initiative’s largest market cannot enhance its trade volumes with other BIMSTEC constituents, deeper trade integration will be limited to rhetoric alone. Given the size of India’s market and its large trading volume with other Asian and extra-regional economies such as the United States and the European Union, we believe that one of the best ways to invigorate regional trade is through India’s leadership. India can serve as a bridge between the two regions if it leads the way vis-à-vis reducing red tape domestically and heading the negotiations on the BIMSTEC FTA. However, given India’s track record of adding export restrictions and protectionist measures, including its decision to withdraw from the RCEP, there remains a great deal of skepticism about India’s enthusiasm to develop an FTA.

While it is true that New Delhi has shown a more protectionist hue, it does not stand to reason to allow Beijing to make greater inroads into both regions. The failure to establish the trade pillar under the IPEF, alarmingly, shows that the United States is not ready to undertake trade policies that will substantially rival China’s position in the Indo-Pacific.[9] A leader is needed to counter China’s economic influence in the region, and for India, which wants to establish itself as a leader of the Global South, a BIMSTEC FTA could be its opportunity to do so. If Indian policymakers’ factor in the necessity of counterbalancing China’s economic influence and recognize that the IPEF’s staying power also depends on deeper economic integration between regional landscapes, it is possible to anticipate India playing a greater role in realizing a BIMSTEC FTA.

In addition to BIMSTEC’s ongoing incomplete FTA, other economic projects have to be completed to ensure connectivity and infrastructure development. It is crucial to ensure that these projects uphold robust regulatory frameworks, address social and environmental concerns, and develop human capacity to effectively manage cross-border trade. This is necessary to enhance regional connectivity and expedite the implementation of key infrastructure projects, such as the Asian Trilateral Highway to develop connectivity with Southeast Asia and the BBIN Motor Vehicles Agreement for greater inter-regional integration. The BIMSTEC Master Plan for Transport Connectivity (2018-2028), in this context, is a welcome development to improve transport linkages between its constituents.[10] Together with the assistance of the Asia Development Bank, the plan hopes to spur connectivity in the road, railway, maritime port, and airport infrastructure through a 22 billion USD investment plan.[11] Alongside the development of physical infrastructure, BIMSTEC also needs to take proactive measures to harmonize and simplify border and customs clearance processes so that the infrastructure built through the master plan is made effective.

Agricultural trade can become a key driver of economic growth for the region. In the BIMSTEC region, more than 712 million people are identified to be food insecure.[12] Current efforts at promoting agriculture and food security remain limited and insufficient to deal with the climate-affected, post-pandemic world. Earlier this year, India imposed a ban on non-basmati white rice exports and implemented a twenty percent duty on parboiled rice exports. The list of export bans has also increased recently to include onions as well. This disruption in the staple rice market has led to significant economic and social consequences for BIMSTEC economies (excluding Thailand and Myanmar), which import over seventy percent of their rice from India. This not only heavily affected trust in India as a reliable economic partner but also its political legitimacy as a leader of the Global South. This reiterates a pressing need for BIMSTEC to recalibrate its approach to manage regional supply chain connectivity and establish food security to mitigate disruptions to rice exports/imports. BIMSTEC can consider drawing lessons from Thailand’s activities in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS). Working with developing ASEAN economies, Thailand was heavily involved in promoting sub-regional economic integration with the GMS partners.[13] This included simplifying procedures for cross-border and transport and fostering pragmatic political caucus discussion to coordinate priorities and convey national interests. By prioritizing agricultural policies that ensure domestic food security while facilitating agricultural trade within the region, BIMSTEC can foster greater food security and promote economic growth.

Another area to boost connectivity is to promote the region’s clean energy transition. Across BIMSTEC, electrical accessibility and connectivity remain relatively low. Currently, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, and Bhutan, have achieved a hundred percent or close to a hundred energy access; and the other BIMSTEC member states are slowly getting there.[14] The majority of the energy supply is heavily dependent on fossil fuels. Facilitating bidirectional cross-border green energy trade can significantly benefit the developing BIMSTEC economies. Bhutan and Nepal possess a huge hydropower potential that exceeds their domestic requirements, presenting an opportunity for export to meet India’s rising energy demands. In particular, Nepal’s hydropower potential has also garnered the interest of China, which has already been strategically involved in the hydropower infrastructure development of the country.[15] This would invariably increase Chinese footprints in the region and potentially undermine India’s strategic geopolitical interests.

Simultaneously, neighboring BIMSTEC countries can leverage India’s rapidly expanding renewable energy sector to address their energy security concerns and promote sustainable economic growth. This regional connectivity project crucially requires the establishment of cross-border grids equipped with long-distance cables and energy infrastructure capable of transmitting electricity seamlessly across the region.

Looking Ahead

South Asia remains one of the least integrated regions in the world in terms of trade and people-to-people contact[16] and in recent weeks, Maldives has begun tilting away from New Delhi and towards Beijing.[17] Some observers have added that India can no longer depend upon USA’s leadership in the Indo-Pacific operation theatre, particularly in the domain of international/regional trade networks.[18] India, therefore, needs to assert leadership in the region by harmonizing domestic politics with its foreign policy and prevent domestic pressures from undermining its long-term foreign policy goals.[19] To realize its aspirations of becoming a regional leader, India’s foreign policy should continue advocating for regional economic connectivity. This involves calibrating its economic policies to align with the interests of neighboring BIMSTEC countries and actualizing its Neighborhood First policy.

Since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative, China has significantly extended its economic influence in South Asia and the larger Indian Ocean sphere by funding key infrastructure development projects. India’s leadership in BIMSTEC could be the driving force to counter China’s influence by enhancing Indian-led regional connectivity, strengthening economic integration, and facilitating cross-border trade. The potential of the BIMSTEC remains intact and if its members can enhance cooperation through these less politically sensitive domains, the prospect of deeper regional integration remains bright.

Shakthi De Silva is a Non-Resident Vasey Fellow at Pacific Forum International (USA) and a Visiting Lecturer at the Royal Institute of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Mae Chow is a Research Assistant attached to the Centre on Asia and Globalization (CAG) at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Works Cited

[1] “Why #OneSouthAsia?”, The World Bank, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/south-asia-regional-integration/trade

[2] Prabir De, “Regional Integration in Bay of Bengal region in post-Covid-19 period”, ARTNet Working Paper Series, January 2021, Bangkok:UNESCAP.

[3] “BIMSTEC trade facilitation strategic framework 2030”, Asian Development Bank, 2022, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/850371/bimstec-trade-facilitation-strategic-framework-2030.pdf

[4] “Navigating digital transformation: the crucial role of chief digital officers in crafting innovating futures,” The Economic Times, 30 November 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/c-suite/navigating-digital-transformation-the-crucial-role-of-chief-digital-officers-in-crafting-innovative-futures/articleshow/105628750.cms

[5] Eric Martin, “India Opts Out of Trade Talks with US-Led Indo-Pacific Group”, Bloomberg, 10 September 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-09/india-avoids-trade-negotiations-with-us-led-indo-pacific-group?embedded-checkout=true

[6] Yoshifumi Fukunaga, “ASEAN’s leadership in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”, Asia & The Pacific Policy Studies, 2015, 2(1), 103-115.

[7] Yves Tiberghien, “Rules and order as national interest: Explaining Japan’s leadership in the CPTPP and other trade initiatives, SPPGA Joint Policy Paper Series, 2018, https://sppga.ubc.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/07/Tiberghien_Japan-LIO-revised.pdf

[8] Nisha Tanega, Shravani Prakash & Pallavi Kalita, “India’s role in facilitating trade under SAFTA”, ECONSTOR, 2013, (263), 1-18

[9] Chris Dixon and Bob Savic, “After APEC: Whither US Leadership on Trade?’, The Diplomat, 15 December 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/12/after-apec-whither-us-leadership-on-trade/

[10] “BIMSTEC Master Plan for Transport Connectivity”, ADB, 2022, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/740916/bimstec-master-plan-transport-connectivity.pdf

[11] Ibid

[12] Abul Kamar, Devesh Roy Mamata Pradhan & Sunil Saroj, “India’s rice export restrictions and BIMSTEC countries: Implications and recommendations”, International Food Policy Research Institute, 2023, https://www.ifpri.org/publication/indias-rice-export-restrictions-and-bimstec-countries-implications-and-recommendations

[13] Susannah Patton, “Thailand’s efforts to build Mekong Bloc deserve support”, Nikkei Asia, 4 October 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Thailand-s-efforts-to-build-Mekong-bloc-deserve-support

[14] Maitreyi Karthik & Rajiv Panda, “BIMSTEC region can provide green, affordable energy access to all”, DownToEarth, 03 March 2023, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/renewable-energy/bimstec-region-can-provide-green-affordable-energy-access-to-all-88065

[15] Nara Sritharan & Kritika Jothishankar, “The Great Himalayan Chessboard: China, India and the geopolitical gambit in Nepal, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 06 December 2023, https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/12/great-himalayan-chessboard-china-india-and-the-geopolitical-gambit-in-nepal/

[16] “South Asia least integrated region in world: ICCB”, The Business Standard, 20 July 2023, https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/south-asia-least-integrated-region-world-report-668658

[17] Meera Srinivasan, “View From India: The persisting Maldives challenge”, The Hindu, 05 February 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/the-persisting-maldives-challenge/article67813763.ece

[18] Jabin Jacob, “India is not stepping up to the challenge of countering China”, Deccan Herald, 25 October 2023, https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/china-india-belt-and-road-initiative-pakistan-sri-lanka-cpec-balochistan-2740682

[19] Sumit Ganguly, “How india’s Domestic Politics Impede Its Foreign Policy”, Foreign Policy, 5 February 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/05/india-foreign-policy-drift-modi-politics-basrur/.