Dr. Tricia Bacon is an Associate Professor at the School of Public Affairs at American University.

Dr. Elizabeth Grimm is an Associate Professor of Teaching in the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University.

One of the singular challenges for a terrorist organization is how to transition to another leader after the founder’s death. For the counterterrorism (CT) community, the question of succession presents opportunities for disruption by creating space to sow internal discord and, potentially, the chance to degenerate the group in its entirety. For this reason, CT policymakers have embraced the tactic of leadership decapitation, or targeting terrorist leaders for assassination, and CT academic debates have largely focused on whether this tactic is effective. But policymakers and researchers have paid little attention to the differing leadership styles of the successors that take over after terrorist leaders’ deaths, and the strengths and weaknesses that each type of successor possesses. Our research aims to fill this gap to better understand the distinct roles of terrorist organization founders, their successors, and how these roles evolve over time. In our recent book, Terror in Transition: Leadership and Succession in Terrorist Organizations, we ask: how do founding terrorist leaders establish the how and the why of their organizations, and how do their successors continue that trajectory or alter it? In this article, we then examine the distinct CT vulnerabilities associated with each archetype of successor to terrorist organization founders.

When trying to understand the impact of a terrorist leader’s death, scholars implicitly analyze how the loss changes the how and why of the organization. The how refers to changes to tactics or resource mobilization, while the why refers to changes to the group’s framing. We developed a theory that terrorist group founders craft the organizations’ how and why, and each successor defines their leadership style based on how they position themselves relative to the original how and why.

The why is the group’s declared objectives. A terrorist leader’s ability to continue an organization and persist in fighting for the cause reflects his role in framing the why of an organization. The how of a terrorist group refers to the means they choose to achieve the why. How will groups mobilize resources to achieve their mission? What tactics will they use, both operational and non-operational? If removing the leader hinders the operational effectiveness of the group, such as the lethality of its attacks, then the leader must have played a crucial role in the decision-making and guidance of these operations—aspects of the organization’s how.

To construct our typology of successors, we conducted comprehensive, time-bound case studies of four organizations, which spanned four founders and eight successors. To identify the case studies and test our findings, we developed a wider sample of religious terrorist organizations that had experienced at least one leadership transition. We included Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Jewish, Sikh, and Christian organizations, including some white supremacist groups with religious components to their ideology, like the Second Klan, which terrorized the United States in the 1920s. The final sample included thirty-three organizations spanning over one hundred years, more than twenty nation-states, and over ninety different leaders.

Types of Successors

After terrorist founders have created their organization’s how and why, terrorist successors decide to proceed with either incremental changes that evolve the group’s fundamental goals and means, or discontinuous changes that significantly upend how the group frames its mission, the tactics it employs, the way it mobilizes resources, or all these characteristics. We divided the types of terrorist leader successors that we encountered in our research into five archetypes.

Caretaker

When the successor seeks to continue the founder’s trajectory with only incremental changes in framing, tactics, and resource mobilization, the leader is a caretaker. Caretakers are likely to emerge when the successor is related to the founder. Sirajuddin Haqqani, for example, derived a great deal of legitimacy in the Haqqani Network from his ties to his father, founder Jalaluddin Haqqani.

Signaler

A successor who makes discontinuous changes to the framing—the rhetoric, propaganda, and messaging used to explain a group’s why—is a signaler. Isnilon Hapilon’s 2014 pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State when he was the leader of Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)—a Muslim terrorist group operating in the southern Philippines that seeks a distinct Muslim state in this region—is evidence of signaling behavior. In so doing, Hapilon sought to align ASG’s framing with the Islamic State’s so-called Caliphate during a time when the Islamic State enjoyed tremendous jihadist cachet.

Fixer

When a successor oversees discontinuous changes to tactics and resource mobilization, which defines a group’s how, the result is a fixer. Fixers might turn to new tactics and tools, such as suicide bombings, female suicide bombers, or improvised explosive devices. Fixers might look to different means to raise money or recruit members. Under Khaled Meshaal’s leadership of Palestinian militant group Hamas following the 2004 death of its founder, Sheikh Yassin, Meshaal sought to emphasize the importance of electoral politics to their cause, thus shifting the group’s tactics to embrace political participation as a means of change.

Visionary

A leader who makes discontinuous changes to framing, tactics, and resource mobilization—both the why and the how—is a visionary. A leader who proclaims the formation of a state and introduces governance to a group’s repertoire of action would be a visionary successor. Visionaries often both introduce and reflect the divisiveness of the groups they lead, such as Fumihiro Joyu, one of the successors of Japanese apocalyptic cult Aum Shinrikyo. Fumihiro Joyu sought to dramatically change the group’s framing and tactics. In an interview with the New York Times in 2000, Joyu apologized for lying to the Japanese people through his denials that Aum had any connection to the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack. He further argued that the sect had already taken several major steps toward transforming itself; this included changing the name from Aum to Aleph, which signifies a new beginning, and distancing the group from its founder, Shoko Asahara.

Figurehead

When leaders do not actively choose the path of change or continuity, they are figureheads. In this case the leader is nominally in charge, but they are unwilling or unable to make key decisions for the organization. For example, while ailing and facing rivals who sought to oust him, al-Shabaab’s Abu Ubaydah struggled to maintain the authority he established between 2014 and mid-2017. Due to his health concerns, Ubaydah has adopted a figurehead role since that time.

Exploiting Vulnerabilities

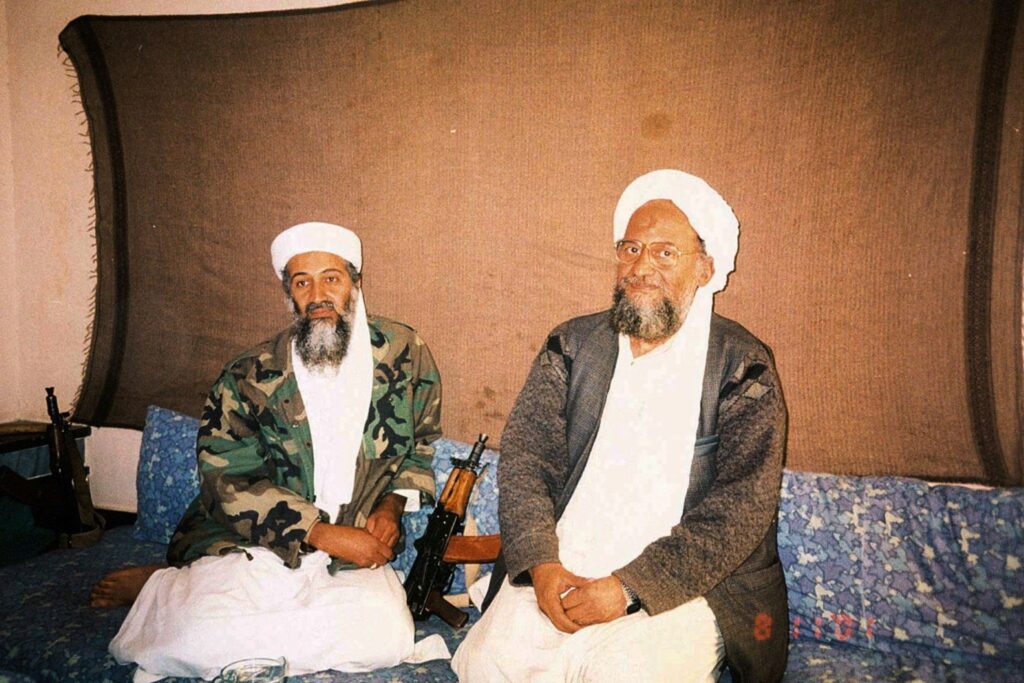

Each of the successor archetypes possess distinct weaknesses that CT efforts can exploit. The most durable successor of the archetypes studied here is the caretaker. By making only minimal changes to the framing, tactics, and resource mobilization that the founder established, the caretaker ensures stability. As a result, the primary opportunity for CT disruption is during the period of uncertainty before the caretaker is made the leader. Caretakers are not without vulnerabilities, however. Once a caretaker is at the helm, he risks failing to adapt to changes in the overall political and military landscape. This conservative style of leadership can render an organization poorly positioned to operate under changing circumstances. For example, Ayman al-Zawahiri was a steadfast caretaker of Osama bin Laden’s goals for al-Qaida in the decade following bin Laden’s death, yet the group may have benefitted from a different leader better poised to gain global attention and revitalize a lagging recruitment base.

In the cases of fixers, signalers, and visionaries, there are opportunities to discredit such leaders by highlighting their changes to the organization’s original framing and methods, which members may perceive as a betrayal of the group’s original mission. Notably, in interviews with disengaged white supremacist extremists, researchers have identified frustration with hypocrisy as one of many drivers of disillusionment with such movements. But exposing these hypocrisies is no easy task. The history of strategic persuasion to counter extremism is fraught with mistakes across the ideological spectrum, and the United States should strive to improve both governmental coordination and outreach to the private sector.

Fixers may present opportunities for CT officials to publicly expose the mismatch between their chosen tactics and the founder’s blueprint. For example, in the mid-1990s, CT pressure within Egypt and forceful calls from Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) members to renew attacks against the Egyptian government persuaded Zawahiri to adapt the group’s how. EIJ began attacking symbols of the Egyptian state, such as the Egyptian Prime Minister in Cairo and the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad by any means possible, including suicide bombings. This was a far cry from EIJ founder Muhammad Abd al-Salam Faraj’s original plan for a coup and revolution. This change in tactics increased civilian deaths and damaged EIJ’s image among Egyptians. Public opinion dramatically soured against the group after the death of a young schoolgirl in an EIJ bombing in 1993. Zawahiri’s fixer-style attempts to target the Egyptian government from abroad further turned public opinion and even some of his followers against him, challenging the workings of an already strained EIJ. Moreover, the change in tactics alienated not only the Egyptian public but also EIJ members, some of whom viewed the move to suicide bombings as a step too far. In this case, exposing the hypocrisy that underpins the how can erode not just constituent support, but can also foment internal cleavages.

In the cases we analyzed, there was a wider range of outcomes under fixers than signalers and visionaries. Fixers may adapt their groups to changing environments or change tactics to reflect developments in the organization’s capabilities. Nonetheless, there are certain types of “fixes” that may provoke internal dissension or alienate a group from its constituents, such as adopting suicide operations. In addition, when undertaking operational changes, groups risk committing operational errors, especially when their new tactics are more violent and threatening to civilians. Fixers, then, provide an opening for CT actors to magnify such missteps.

Signalers—and even more so, visionaries—can be divisive leadership figures. Their actions can create rifts within a group and alienate it from its allies and constituents. After al-Qaida in Iraq founder Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s death, his successors Abu Ayyub al-Masri and Abu Umar al-Baghdadi acted as signalers by declaring an Islamic state in Iraq. This was met with dismay by al-Qaida, repudiated by the rival groups it hoped to induce into cooperation, and rejected by the Sunni tribes it sought to govern. One could also look at a visionary leader like Abdelmalek Droukdel, who presided over the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat’s rebranding to al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb. His decision to affiliate with al-Qaida and the group’s shift to targeting civilians and escalating attacks highlights the potential divisiveness of visionaries. These changes from the founder’s original foundation can result in internal dissension. The divisive nature of visionary leaders may thereby increase the success of CT strategies that offer terrorists an off-ramp. For example, amnesty initiatives or other CT efforts like deradicalization programs may provide members with a way out of an organization that they perceive as having fundamentally diverged from what they signed up for.

Finally, a group led by a figurehead is like a ship without a captain. The lack of leadership may increase the likelihood that others in the group will seek to perpetuate continuity or implement changes in an uncoordinated fashion, thereby working at cross-purposes or even in competition with one another. Indeed, under Sayyed Imam al-Sharif’s figurehead leadership of EIJ, Ayman al-Zawahiri was driving the changes in the group or acquiescing to internal pressure for certain actions. Sharif’s absentee leadership came at a time when EIJ was struggling to survive, creating the opening for Zawahiri to impose his views. Without direction from the leader, a group can come adrift or become riven with divisions. Thus, in some cases there may be utility to leaving figurehead leaders in place, despite the clear policy preference for leadership decapitation.

Conclusion

While the academic literature on the effectiveness of leadership decapitation has flourished, efforts to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the successors that emerge after a leader is killed have been lacking. Studying successors in relation to founders moves the scholarship beyond debates over the utility of leadership decapitation and toward a deeper understanding of how terrorist leaders’ deaths affect their organizations. Effectively capitalizing on leadership succession requires identifying the successor’s leadership style and thus determining which distinct vulnerabilities CT policymakers can exploit.

Works Cited

Tricia L. Bacon and Elizabeth Grimm, Terror in Transition: Leadership and Succession in Terrorist Organizations (Columbia University Press, 2022). http://cup.columbia.edu/book/terror-in-transition/9780231192255.

Gustaf Forsell, “Blood, Cross, and Flag: The Influence of Race on Ku Klux Klan Theology in the 1920s,” Politics, Religion, and Ideology 21, no. 3 (August 2020): 269-287, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21567689.2020.1809384.

“Most Wanted: Sirajuddin Haqqani,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/terrorinfo/sirajuddin-haqqani.

“Abu Sayyaf Group,” Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/abu-sayyaf-group.

Eben Kaplan, “Profile of Khaled Meshal,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 13, 2006, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/profile-khaled-meshal-aka-khalid-meshaal-khaleed-mashal.

Calvin Sims, “Under Fire, Japan Sect Starts Over,” New York Times, February 28, 2000, https://www.nytimes.com/2000/02/28/world/under-fire-japan-sect-starts-over.html.

“Al Shabaab Leader’s Physical Health a Concern to His Deputies,” Nation, April 20, 2018, https://nation.africa/kenya/videos/news/al-shabaab-leader-s-physical-health-a-concern-to-his-deputies-1260674.

Sara Harmouch, “The Question of Succession in al-Qaeda,” War on the Rocks, September 29, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/09/the-question-of-succession-in-al-qaeda/.

Mehr Latif et al., “Why White Supremacist Women Become Disillusioned, and Why They Leave,” The Sociological Quarterly 61, no. 3 (July 2, 2020): 367–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2019.1625733.

Peter Simi et al., “Anger from Within: The Role of Emotions in Disengagement from Violent Extremism,” Sociology Faculty Articles and Research, January 1, 2019, https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/sociology_articles/53.

Michael Jensen, Patrick James, and Elizabeth Yates, “Contextualizing Disengagement: How Exit Barriers Shape the Pathways Out of Far-Right Extremism in the United States,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, (May 4, 2020): 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1759182.

Rosa Brooks, “Evolution of Strategic Communication and Information Operations Since 9/11: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities of the House Committee on Armed Services, 112th Congress, Statement of Rosa Ehrenreich Brooks,” Congressional testimony, July 12, 2011, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cong/115.

Lawrence Wright, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, 1st ed. (New York: Knopf, 2006), https://www.lawrencewright.com/books/the-looming-tower-al-qaeda-and-the-road-to-9-11.

Holly Fletcher, “Egyptian Islamic Jihad,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 2008, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/egyptian-islamic-jihad.

Khalil Gebara, “The End of Egyptian Islamic Jihad?” Terrorism Monitor 3, no. 3 (May 2005), https://jamestown.org/program/the-end-of-egyptian-islamic-jihad/.

“The Islamic State,” Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/islamic-state.

Christopher S. Chivvis and Andrew Liepman, “North Africa’s Menace: AQIM’s Evolution and the U.S. Policy Response,” RAND Corporation, September 9, 2013, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR415.html.

Audra Grant, “The Algerian 2005 Amnesty: The Path to Peace?” Terrorism Monitor 3, no. 22 (November 2005), https://jamestown.org/program/the-algerian-2005-amnesty-the-path-to-peace/.

Lawrence Wright, “The Rebellion Within,” The New Yorker, May 2008, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/06/02/the-rebellion-within.